[ Envirowatchers ] [ Main Menu ]

16669

From: Alan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: India air pollution at 'unbearable levels', Delhi minister says

URL: India air pollution at 'unbearable levels', Delhi minister says

|

'chemtrail' believers should heed good advice from Indian govt and cut down on junk food, take less flights, and eat more carrots. Air pollution in the north of India has "reached unbearable levels," the capital Delhi's Chief Minister Arvid Kejriwal says. In many areas of Delhi air quality deteriorated into the "hazardous" category on Sunday with the potential to cause respiratory illnesses. Authorities have urged people to stay inside to protect themselves. Mr Kejriwal called on the central government to provide relief and tackle the toxic pollution. Schools have been closed, more than 30 flights diverted and construction work halted as the city sits in a thick blanket of smog. Delhi Health Minister Satyendar Jain advised the city's residents to "avoid outdoor physical activities, especially during morning and late evening hours". The advisory also said people should wear anti-pollution masks, avoid polluted areas and keep doors and windows closed. How bad is the smog? Levels of dangerous particles in the air - known as PM2.5 - are far higher than recommended and about seven times higher than in the Chinese capital Beijing. An Indian health ministry official said the city's pollution monitors did not have enough digits to accurately record pollution levels, which he called a "disaster". Harsh Vardhan, the union minister for health and family welfare, urged people to eat carrots to protect against "night blindness" and "other pollution-related harm to health". Meanwhile, Prakash Javadekar, the minister of the environment, suggested that you should "start your day with music", adding a link to a "scintillating thematic composition". What's caused the pollution? A major factor behind the high pollution levels at this time of year is farmers in neighbouring states burning crop stubble to clear their fields. This creates a lethal cocktail of particulate matter, carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide - all worsened by fireworks set off during the Hindu festival Diwali a week ago. Vehicle fumes, construction and industrial emissions have also contributed to the smog. Indians are hoping that scattered rainfall over the coming week will wash away the pollutants but this is not due until Thursday. |

16670

From: Eve, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Re: India air pollution at 'unbearable levels', Delhi minister says

|

The Green Revolution Delhi smog: Foul air came from India's farming revolution Many participants in the Delhi half marathon on Sunday wore anti-pollution masks If there was a gold medal for bad air, Delhi would be hard to beat. Yet, despite high levels of air pollution, more than 30,000 people, many wearing masks, took part in the capital's half marathon on Sunday. Organisers said they used devices on the route to transmit radio frequency waves to clear the air, but scientists were sceptical of these claims. Delhi's marathon, ironically, marked the beginning of the city's smog season. But it has been creeping up on the capital for a few weeks now. A fortnight ago, Nagendar Sharma was returning to Delhi from the hill station city of Shimla when he spotted smoke rising from the farms alongside the highway. It looked like someone had picked up a box of matches and set the earth on fire. Lack of winds meant that the acrid smoke hung in the air. Mr Sharma, the Delhi-based media adviser to the capital's chief minister, was driving through Haryana, barely 70km (43 miles) from the capital. When he stopped his vehicle to investigate he found that the farmers had begun to burn the stubble left over from harvesting rice. They said they had to remove the residue in three weeks to prepare the farms to sow wheat. They were burning the crop stubble as they could not afford the expensive machines that would remove them. "It's the same old story. Every year," Mr Sharma said. Every year, around this time, residents of Delhi wake up to a blanket of thick, grey smog. Pollution levels reach several times the World Health Organisation's recommended limit. Last year, doctors declared a state of "medical emergency"; and hospitals were clogged with wheezing men, women and children. Levels of tiny particulate matter (known as PM 2.5) that enter deep into the lungs reached as high as 700 micrograms per cubic metre in some areas. The WHO recommends that the PM2.5 levels should not be more than 25 micrograms per cubic metre on average in 24 hours. Last winter Air Quality Index (AQI) recordings consistently hit the maximum of 999 - exposure to such toxic air is akin to smoking more than two packs of cigarettes a day. The city becomes what many call a "gas chamber". "This marks the beginning of the Great Smog that goes on to last for about three months, even though the crop residue burning lasts a few weeks. It is during this period that air quality indices hit their maximum possible limits, when visibility drops drastically, when regions even far away - such as Delhi - smell of burning gas," says Siddharth Singh, energy expert and author of a book soon to be published, The Great Smog of India. And although there are other reasons - construction dust, factory and vehicular emissions - it's mainly crop residue that has emerged as one of the main triggers for the smog. More than two million farmers burn 23 million tonnes of crop residue on some 80,000 sq km of farmland in northern India every winter. The stubble smoke is a lethal cocktail of particulate matter, carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide. Using satellite data, Harvard University researchers estimated that nearly half of Delhi's air pollution between 2012 and 2016 was due to stubble burning. Another study attributed more than 40,000 premature deaths in 2011 to air pollution arising from crop residue burning alone. But it wasn't always like this. In Mr Singh's telling, the deadly pea-souper is result of the "evolution of the farming operations, government policy and changing labour markets" sparked by the "green revolution" in India in the late 1960s and 1970s. The "green revolution" allowed a country wracked by famines, hobbled by un-irrigated farms and dependency on food aid to produce enough grain to feed its people. The northern states of Punjab and Haryana turned into breadbaskets, producing enough rice and wheat for the country. Wheat is sown and harvested during winters, and rice to coincide with the monsoon season in July and August. Price support for crops, high-yielding seeds, expanded irrigation, official farming timetables and the introduction of combine harvesters - which combined the jobs of cutting and threshing the crop in order to produce processed grain in a matter of seconds - were the catalysts of this modern farming revolution. The "green revolution" was an unqualified success in giving India much-needed food security. It led to vast increases in wheat and rice production, but also ended up polluting air and depleting groundwater. "That a revolution in agriculture was necessary is by itself not up for debate. What the revolution and the subsequent policies did, however, was contribute to the creation and timing of the air pollution crisis and also to the rapidly depleting groundwater levels; this has been termed as an 'agro-ecological' crisis," says Mr Singh. Farmers burn crop residue because the stubble left behind after the combine harvesters have done their job is sharper and taller than it otherwise would be, potentially injurious to farmers and not good fodder for animals. If they do not remove the stubble, straw gets stuck in the machines that plant the rice crop. The smoke remains in the air, causing severe health issues for people So they simply set fire to the farmland to get the soil ready quickly for the next crop, as Mr Sharma saw on the highway to Delhi. According to Siddharth Singh, there are some 26,000 combine harvesters in use in India, most of them in northern India. They are responsible for a practice that is now a major contributor to air pollution. The government has tried to solve this with "happy seeders", which are attachments mounted on tractors that help plant wheat seeds without getting jammed by rice straw stubble from the previous crop. But they are expensive - upwards of 130,000 rupees (£1,363; $1,769) and diesel-guzzlers - and remain out of reach for most farmers, who own small plots of land. During the smog season last year, according to Mr Singh, there were about 2,150 of these machines in Punjab and Haryana as against an estimated requirement of more than 21,000. Another machine called the "super straw management system" which chops and spreads the stubble evenly is also effective but expensive for the majority of farmers. Mr Singh reckons if crop stubble burning is to be stopped fully within five years, 12,000 "happy seeders" will need to be purchased every year. India, he believes, needs a second "green revolution which would be a technological one - one that adequately deals with agricultural shock to air quality". Until that happens, Delhi's foul air will continue to poison its 18 million people. |

16671

From: Eve, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Re: India air pollution at 'unbearable levels', Delhi minister says

|

image caption: Every year, through October, thousands of farmers across Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh set fire to an estimated 23 million tonnes of paddy straw. Photo: Sayantan Bera/Mint The real reason behind the north Indian smog 4 min read . Updated: 22 Oct 2018, 10:02 AM IST Vivek Kaul The pollution problem is about the allocation of right resources in the right areas. It is a political problem more than an economic one Delhi starts to become dystopian, a few weeks before Diwali, and this continues for around a month after the festival of lights. The conventional explanation for the Delhi smog (in fact, it impacts large parts of North India) is the burning of rice straw by the farmers of Punjab (primarily), Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh. The farmers use mechanical harvesters in order to cut, thresh and clean rice from paddy. The problem is that these harvesters leave six to eight inch long straws on the field, which cannot be used as animal feed because of the high silica content, which the cattle cannot digest. Further, the fields need to be prepared for the winter wheat crop in a matter of two to three weeks. There are machines available which can take care of the straws, but machines cost money, whereas, all that is needed to start a fire is a matchstick. Of course, there is the threat of fines for those who choose to set their fields on fire. But it still makes sense for a farmer to start a fire, even if he gets caught and has to pay a fine, given that machines are expensive. Also, most farmers don’t want to spend money on machines that they are likely to use once or twice a year, yet still require maintenance all through the year. This is the conventional explanation of why farmers in Punjab, and other states, burn rice straw and how that causes a cloud of smog across large parts of Northern India. But there is a more important question which no one is asking—Why are semi-arid states like Punjab and Haryana growing rice in the first place? The procurement of rice by the FCI has to move away from Punjab to states like West Bengal and Assam, where it takes less water to grow rice- In 2016-2017, Punjab was the third largest rice producing state after West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. Punjab produced 11.03 million tonnes (mt) of rice, or around a tenth of the total production in the country. The Indian government primarily procures rice and wheat directly from the farmers at a minimum support price. This is done through the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and other state procurement agencies. In 2016-2017, a total of 38.1 mt of rice was procured by the government in the central pool. Punjab contributed 27% or 10.29 mt to this pool. Of the total production of 11.03 mt of rice in the state, more than 93% was acquired by the government. This large procurement is a hangover from the days of the Green Revolution, where the government was trying to incentivize farmers of Punjab to grow more foodgrains to make India sufficient on the food front. Also Read: Economic logic of setting paddy fields on fire All the rice is being grown in a semi-arid region, which ends up using a lot of water. As an official document on the Price Policy for Kharif Crops points out: “If water consumption is measured in terms of per kg of rice, West Bengal becomes the most efficient state, which consumes 2,169 litres to produce one kg of rice, followed by Assam (2,432 litres) and Karnataka (2,635 litres). The water use is high in Punjab (4,118 litres), Tamil Nadu (4,557 litres) and Uttar Pradesh (4,384 litres)." Also, free electricity allows Punjab’s farmers to pump all the groundwater they need to produce rice in a semi-arid region. As Jean Drèze writes in his book Sense And Solidarity—Jholawala Economics for Everyone: “Massive resources have been spent on promoting unsustainable farming patterns in Punjab, Haryana, and other privileged areas." What is the solution to this? First and foremost, free electricity, at least to the medium and large farmers (those who own plots of 4 hectares and above), should be done away with. Of course, given the strong lobby of large farmers in the state, this remains easier said than done. Secondly, the procurement of rice by the FCI has to move away from Punjab to states like West Bengal and Assam, where it takes less water to grow rice. Third, the import duty on rice needs to come down. As the official document on kharif crop price policy for the current fiscal points out: “With some intermittent relaxations, import duty on rice remains at 70-80%. Such a high level of import duty on a water guzzling crop like rice may not be desirable and if import duty on rice is rationalized, it may support crop diversification into much needed crops like oilseeds and pulses." Fourth, the excess procurement of rice in the central pool needs to end. As per stocking norms, as on 1 October, the total amount of rice that needs to be maintained in stock is 10.25 mt. The actual stock is at 18.63 mt. Given that the government is buying more rice than it needs, it encourages the farmers to produce more rice. This needs to stop. Basically, Delhi and Northern India’s smog problem is about the allocation of right resources in the right areas. And given that, it is a political problem more than an economic one. |

Responses:

[16672]

16672

From: Eve, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Dirty air: how India became the most polluted country on earth

|

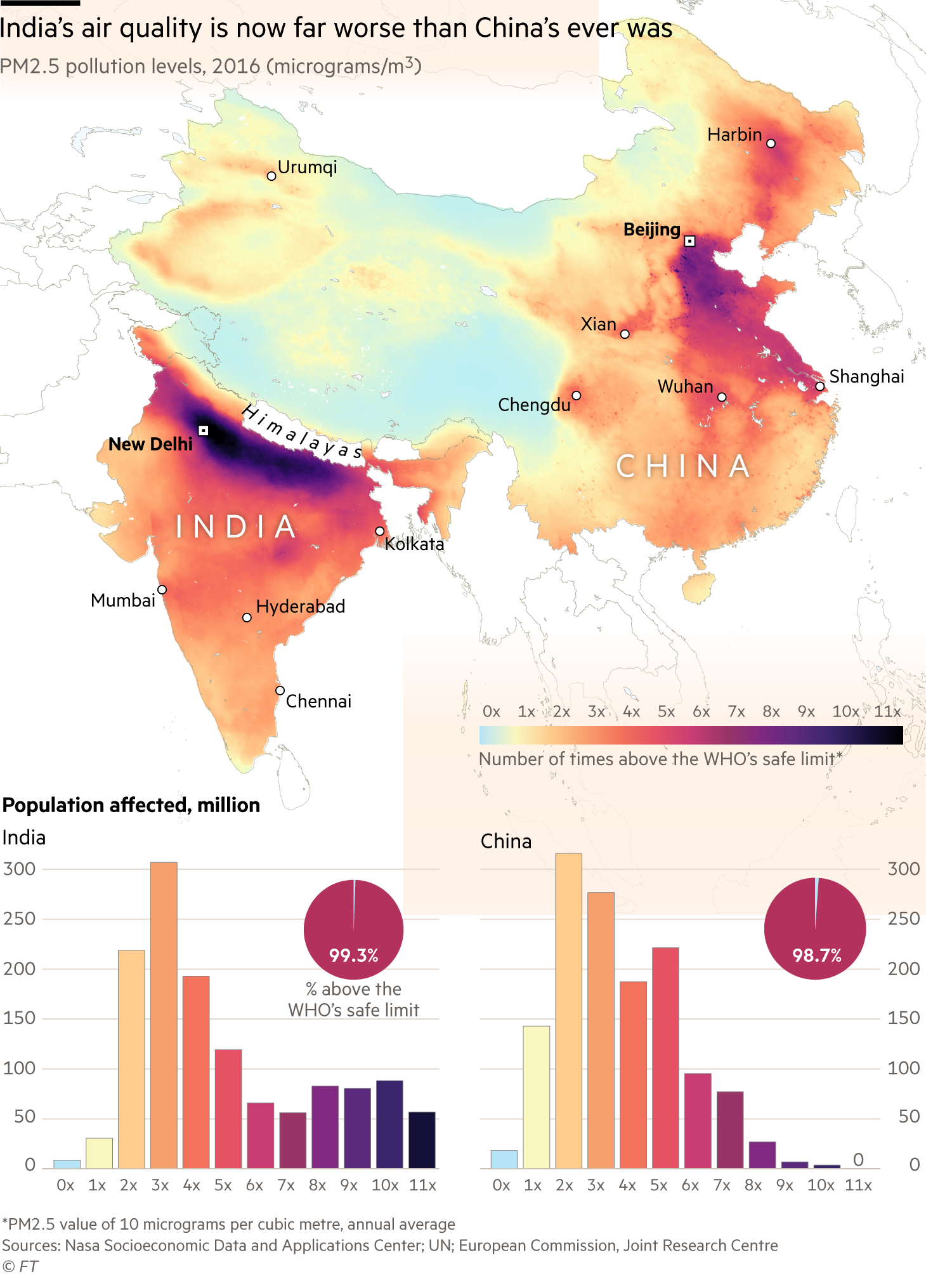

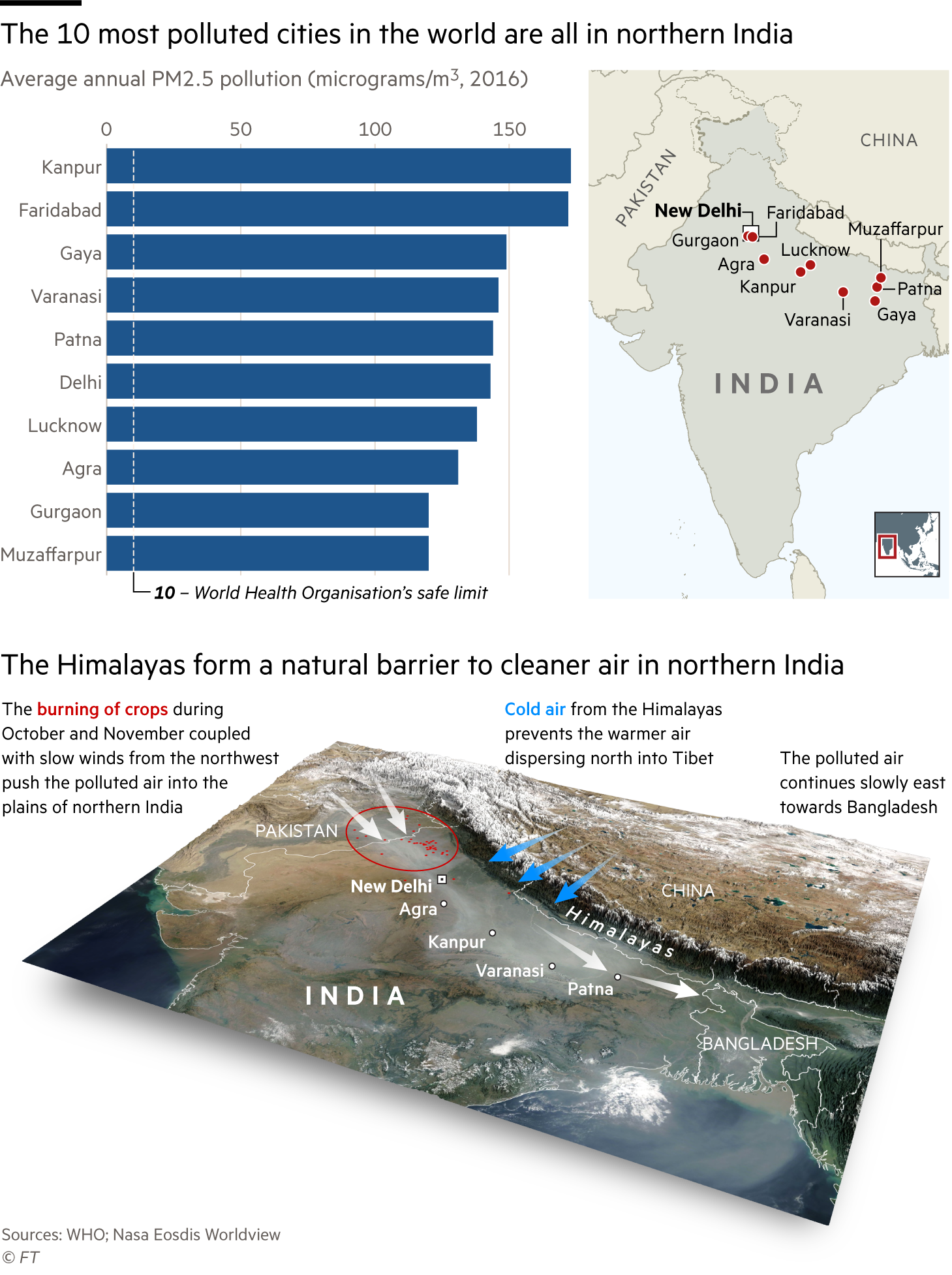

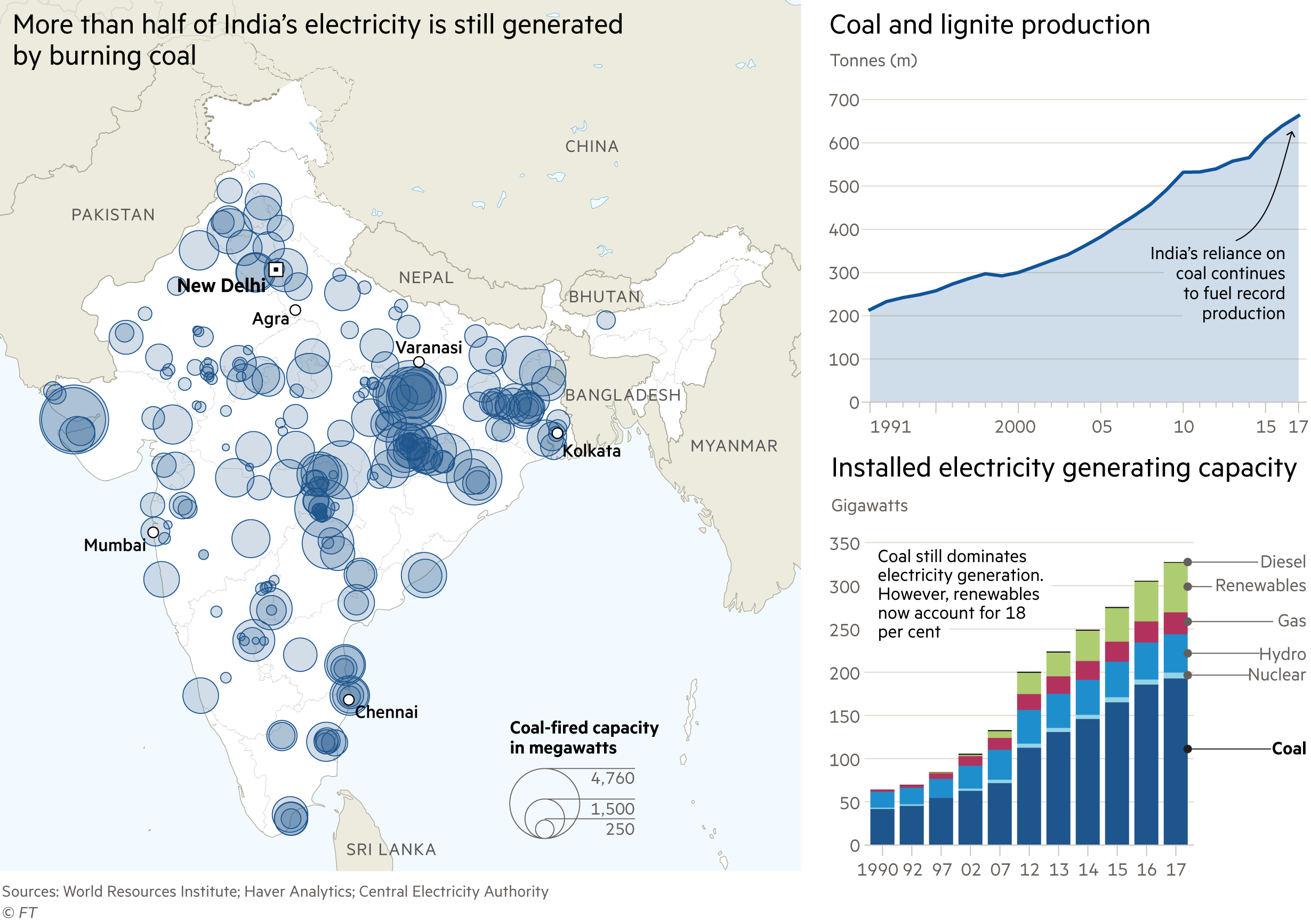

Dirty air: how India became the most polluted country on earth With the situation worse than it ever was in neighbouring China the Modi government is struggling to introduce measures to combat the problem Arvind Kumar, a chest surgeon at New Delhi’s Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, has a ringside view of the toll that northern India’s deteriorating air quality is taking on its residents. When he started practising 30 years ago, some 80 to 90 per cent of his lung cancer patients were smokers, mostly men, aged typically in their 50s or 60s. But in the past six years, half of Dr Kumar’s lung cancer patients have been non-smokers, about 40 per cent of them women. Patients are younger too, with 8 per cent in their 30s and 40s. To Dr Kumar, the dramatic shift in the profiles of lung cancer patients has a clear cause: air fouled by dirty diesel exhaust fumes, construction dust, rising industrial emissions and crop burning, which has created heavy loads of harmful pollutants in the air. Even in teenage lungs, Dr Kumar sees black deposits that would have been almost unthinkable 30 years ago. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — in short, severe lung conditions — is now India’s largest cause of death after heart disease. “If these guys are having black deposits on their lungs as teens, what’s going to happen to them 20 years later?” asks Dr Kumar, who last week launched Doctors for Clean Air to raise awareness about the impact of air pollution. “It’s a silent crisis. It’s an emergency.” The problem is most acute in India but it is not alone. The Financial Times collated Nasa satellite data of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) — a measure of air quality — and mapped it against population density data from the European Commission to develop a global overview of the number of people affected by this type of dangerous pollution. -------- > see graphs at link: https://ig.ft.com/india-pollution/ The results are alarming: not just the number of people breathing in polluted air, but those breathing air contaminated with particulates that are multiple times over the level deemed safe — 10 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic metre — by the World Health Organisation. --------- > graph at link: https://ig.ft.com/india-pollution/ The data show that more than 4.2bn people in Asia are breathing air many times dirtier than the WHO safe limit. It only takes into account areas that are populated to avoid skewing the numbers for countries such as China and Russia that have vast unpopulated regions. Historically China has grabbed most headlines for poor air quality. But as the time-lapse video of PM2.5 pollution between 1998 and 2016 shows, India is now in a far worse state than its larger neighbour ever was. --------- > motion visual at link: http://ig.ft.com/india-pollution/videos/india-china-pollution-large.mp4 https://ig.ft.com/india-pollution/ The 2016 data, the latest available, show that, although both countries have a similar number of people breathing air above the safe limit, India has far more people living in heavily polluted areas. At least 140m people in India are breathing air 10 times or more over the WHO safe limit.  A study published in The Lancet has estimated that in 2017 air pollution killed 1.24m Indians — half of them younger than 70, which lowers the country’s average life expectancy by 1.7 years. The 10 most polluted cities in the world are all in northern India. Top officials in prime minister Narendra Modi’s government have suggested New Delhi’s air is little dirtier than that in other major capitals such as London. Harsh Vardhan, India’s environment minister and a doctor, has played down the health consequences of dirty air, insisting it is mainly a concern for those with pre-existing lung conditions. But that appears to fly in the face of international studies that show that air pollution has a wide-ranging impact, including an elevated risk for heart attacks and strokes, increased risk of asthma, reduced foetal growth, stunted development of children’s lungs, and cognitive impairment. Dr Vardhan has claimed India needed its own research to determine whether dirty air is really harmful to otherwise healthy people — an argument the government also made in the Supreme Court. A study published in The Lancet has estimated that in 2017 air pollution killed 1.24m Indians — half of them younger than 70, which lowers the country’s average life expectancy by 1.7 years. The 10 most polluted cities in the world are all in northern India. Top officials in prime minister Narendra Modi’s government have suggested New Delhi’s air is little dirtier than that in other major capitals such as London. Harsh Vardhan, India’s environment minister and a doctor, has played down the health consequences of dirty air, insisting it is mainly a concern for those with pre-existing lung conditions. But that appears to fly in the face of international studies that show that air pollution has a wide-ranging impact, including an elevated risk for heart attacks and strokes, increased risk of asthma, reduced foetal growth, stunted development of children’s lungs, and cognitive impairment. Dr Vardhan has claimed India needed its own research to determine whether dirty air is really harmful to otherwise healthy people — an argument the government also made in the Supreme Court. Dr Kumar believes New Delhi’s unwillingness to acknowledge the severity of its pollution crisis stems from its reluctance to take strong measures tackle large polluters. Such a crackdown would inevitably upset powerful vested interests in the automotive sector, highly polluting small and medium-sized industries, power plants, construction companies and farmers. And it could hit economic growth ahead of elections next year. “They are not unaware but, despite being aware, they deny,” says Dr Kumar, “The corrective measures that would be needed are unpleasant, and might make them lose votes rather than gain votes.” But environmentalist Sunita Narain, director-general of New Delhi’s Centre for Science and Environment, says official attitudes have shifted since last winter’s catastrophic air emergency, when record pollution levels forced schools to close for several days. “That was a turning point,” says Ms Narain, who has battled India’s air pollution for decades. “There is outrage now against pollution — it is also now much more of a middle-class issue and government is acting because it understands the public health emergency.” Northern India’s geography means that pollution generated in the region is not easily dispersed because the Himalayas form a barrier to the north, preventing poor air from dissipating. “We are sitting in a region where the wind dies in winter,” says Ms Narain. “Think of it like a big, massive bowl. That is why the ability to deal with the sources of the pollution become critical.”  Map and chart showing the ten most polluted cities in the world are all in northern India. Map showing how the Himalayas form a natural barrier to the north of India, making it difficult for the pollution to disperse into southern China The biggest causes are vehicular pollution, industrial emissions, thermal power plants, construction dust, waste burning and millions of poor households’ use of cheap and dirty fuels such as wood and cow-dung for cooking. Then every November, this heavy mix is exacerbated by millions of farmers in the states of Punjab and Haryana burning rice stubble after their harvests, a cheap way to dispose of otherwise worthless straw. Yet Ms Narain says New Delhi has taken “very significant steps to combat pollution”, albeit often under Supreme Court pressure in the past two years. India has advanced the date for stricter fuel and emission norms to 2020, so new vehicles sold after that will be far cleaner. Mr Modi’s government has provided cooking gas cylinders to more than 50m poor households to try to reduce the use of highly polluting biomass cooking fuels, though high gas refill prices means that biomass burning remains a major pollution source. The UN climate change talks in Poland will discuss this week whether developing countries such as India should be treated differently and given more time to meet emissions targets. The Modi administration is making an ambitious push to expand renewable energy capacity, including solar power, to help meet rapidly growing power demand. Increased investment has made renewables India’s second-largest generator of electricity.  Map showing the 246 coal power stations in India with circles sized by capacity. Chart showing India’s coal production going from 200 million tonnes in 1991 to nearly 700 million in 2017. Chart showing India’s electricity generating capacity rising from 60 gigawatts in 1990 to over 300 gigawats in 2017. Coal still accounts for nearly 60 per cent but renewables now are the second largest generator of electricity Yet India’s 246 coal-fired power plants — most of them inefficient and highly polluting — account for 60 per cent of India’s total electricity production, with a combined capacity of 188GW, and coal is likely to dominate the country’s energy mix for decades to come. While India has imposed tough emissions standards for power plants, state utilities, which own many of India’s ageing coal power plants, have failed to comply, though environmentalists are pushing to hold them to account. “The scale of pollution is so high that we will have to do things much more quickly,” Ms Narain says. That’s where Dr Kumar hopes to help, generating more public pressure for change. “We have to somersault from a position where the government fears reprisal if it acts,” he says, “to one where it fears reprisal if it doesn’t.” |

Responses:

None

[ Envirowatchers ] [ Main Menu ]