[ Music and Art ] [ Main Menu ]

12243

From: ryan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Bobby D and the creative lea

URL: https://theconversation.com/bob-dylan-and-the-creative-leap-that-transformed-modern-music-242171

|

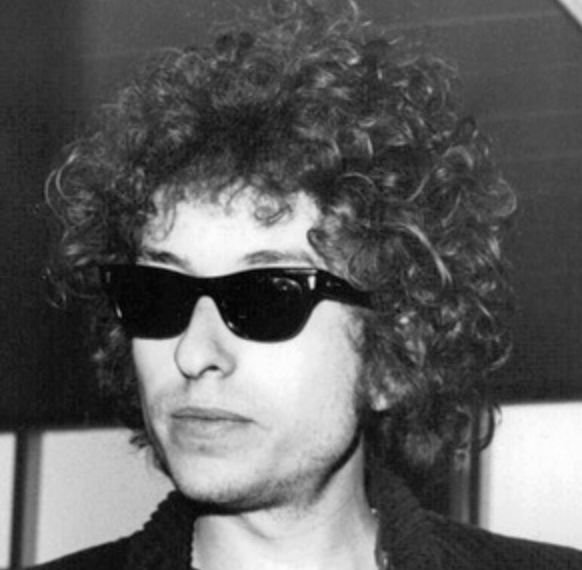

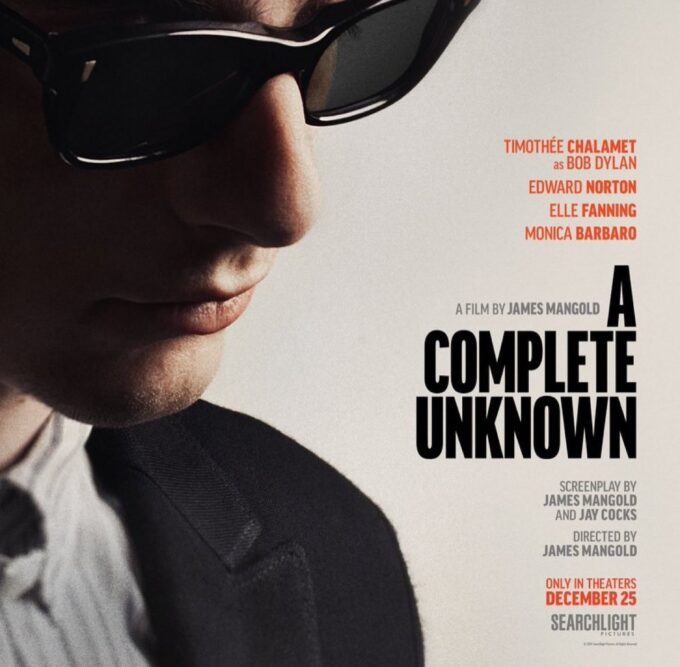

Bob Dylan and the creative leap that transformed modern music Published: December 20, 2024 8:20am EST Updated: December 22, 2024 8:17am EST Author Ted Olson Professor of Appalachian Studies and Bluegrass, Old-Time and Roots Music Studies, East Tennessee State University Dylan in Sweden, 1966. Photo: Wikimedia. We believe in the free flow of information Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license. The Bob Dylan biopic “A Complete Unknown,” starring Timothée Chalamet, focuses on Dylan’s early 1960s transition from idiosyncratic singer of folk songs to internationally renowned singer-songwriter. As a music historian, I’ve always respected one decision of Dylan’s in particular – one that kicked off the young artist’s most turbulent and significant period of creative activity. Sixty years ago, on Halloween Night 1964, a 23-year-old Dylan took the stage at New York City’s Philharmonic Hall. He had become a star within the niche genre of revivalist folk music. But by 1964 Dylan was building a much larger fanbase through performing and recording his own songs. Dylan presented a solo set, mixing material he had previously recorded with some new songs. Representatives from his label, Columbia Records, were on hand to record the concert, with the intent to release the live show as his fifth official album. It would have been a logical successor to Dylan’s four other Columbia albums. With the exception of one track, “Corrina, Corrina,” those albums, taken together, featured exclusively solo acoustic performances. But at the end of 1964, Columbia shelved the recording of the Philharmonic Hall concert. Dylan had decided that he wanted to make a different kind of music. From Minnesota to Manhattan Two-and-a-half years earlier, Dylan, then just 20 years old, started earning acclaim within New York City’s folk music community. At the time, the folk music revival was taking place in cities across the country, but Manhattan’s Greenwich Village was the movement’s beating heart. Mingling with and drawing inspiration from other folk musicians, Dylan, who had recently moved to Manhattan from Minnesota, secured his first gig at Gerde’s Folk City on April 11, 1961. Dylan appeared in various other Greenwich Village music clubs, performing folk songs, ballads and blues. He aspired to become, like his hero Woody Guthrie, a self-contained artist who could employ vocals, guitar and harmonica to interpret the musical heritage of “the old, weird America,” an adage coined by critic Greil Marcus to describe Dylan’s early repertoire, which was composed of material learned from prewar songbooks, records and musicians. While Dylan’s versions of older songs were undeniably captivating, he later acknowledged that some of his peers in the early 1960s folk music scene – specifically, Mike Seeger – were better at replicating traditional instrumental and vocal styles. Dylan, however, realized he had an unrivaled facility for writing and performing new songs. In October 1961, veteran talent scout John Hammond signed Dylan to record for Columbia. His eponymous debut, released in March 1962, featured interpretations of traditional ballads and blues, with just two original compositions. That album sold only 5,000 copies, leading some Columbia officials to refer to the Dylan contract as “Hammond’s Folly.” Full steam ahead Flipping the formula of its predecessor, Dylan’s 1963 follow-up album, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” offered 11 originals by Dylan and just two traditional songs. The powerful collection combined songs about relationships with original protest songs, including his breakthrough “Blowin’ in the Wind.” “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” his third release, exclusively showcased Dylan’s own compositions. Dylan’s creative output continued. As he testified in “Restless Farewell,” the closing track for “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “My feet are now fast / and point away from the past.” Released just six months after “The Times,” Dylan’s fourth Columbia album, “Another Side of Bob Dylan,” featured solo acoustic recordings of original songs that were lyrically adventurous and less focused on current events. As suggested in his song “My Back Pages,” he was now rejecting the notion that he could – or should – speak for his generation. Bringing it all together By the end of 1964, Dylan yearned to break away permanently from the constraints of the folk genre – and from the notion of “genre” altogether. He wanted to subvert the expectations of audiences and to rebel against music industry forces intent on pigeonholing him and his work. The Philharmonic Hall concert went off without a hitch, but Dylan refused to let Columbia turn it into an album. The recording wouldn’t generate an official release for another four decades. Instead, in January 1965, Dylan entered Columbia’s Studio A to record his fifth album, “Bringing It All Back Home.” But this time, he embraced the electric rock sound that had energized America in the wake of Beatlemania. That album introduced songs with stream-of-consciousness lyrics featuring surreal imagery, and on many of the songs Dylan performed with the accompaniment of a rock band. Young man places a guitar with a harmonica hanging from his neck. “Bringing It All Back Home,” released in March 1965, set the tone for Dylan’s next two albums: “Highway 61 Revisited,” in August 1965, and “Blonde on Blonde,” in June 1966. Critics and fans have long considered these latter three albums – pulsing with what the singer-songwriter himself called “that thin, that wild mercury sound” – as among the greatest albums of the rock era. On July 25, 1965, at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan invited members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band on stage to accompany three songs. Since the genre expectations for folk music during that era involved acoustic instrumentation, the audience was unprepared for Dylan’s loud performances. Some critics deemed the set an act of heresy, an affront to folk music propriety. The next year, Dylan embarked on a tour of the U.K., and an audience member at the Manchester stop infamously heckled him for abandoning folk music, crying out, “Judas!” Yet the creative risks undertaken by Dylan during this period inspired countless other musicians: rock acts such as the Beatles, the Animals and the Byrds; pop acts such as Stevie Wonder, Johnny Rivers and Sonny and Cher; and country singers such as Johnny Cash. Acknowledging the bar that Dylan’s songwriting set, Cash, in his liner notes to Dylan’s 1969 album “Nashville Skyline,” wrote, “Here-in is a hell of a poet.” Enlivened by Dylan’s example, many musicians went on to experiment with their own sound and style, while artists across a range of genres would pay homage to Dylan through performing and recording his songs. In 2016, Dylan received the Nobel Prize in literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” His early exploration of this tradition can be heard on his first four Columbia albums – records that laid the groundwork for Dylan’s august career. Back in 1964, Dylan was the talk of Greenwich Village. But now, because he never rested on his laurels, he’s the toast of the world. |

12252

From: ryan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Re: Bobby D and the creative lea

| saw the movie tonight...enjoyed it...brought tears to my eyes several times, remembering those times... |

Responses:

[12253]

12253

From: ryan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Re: Bobby D and the creative leap

|

January 10, 2025 Meet Mr. Dylan Michael Albert Photograph Source: Sharon Mollerus – CC BY 2.0 Perhaps you are aware there is a new movie out titled A Complete Unknown. It addresses the first five years, or thereabouts, in Bob Dylan’s public musical life. I have not yet seen it. I have read some interviews with cast, director, etc., and have seen some excerpts, as well as heard from some friends who have seen it. Timothee Chalamet, who plays Dylan, has reported that he hopes that among other outcomes the movie will introduce Dylan and his words to new generations. Regrettably I can’t now say that my guest for this episode is Bob Dylan here to talk about his words. I can’t even say my guest is Timothee Chalamet here to talk about Dylan’s words. But… Well, I find it remarkable that high school kids, college kids, grown people in their twenties and thirties, even ones who listen to lots of music, often don’t even know who Bob Dylan is. I’ve had two friends who have seen the movie tell me the theatre was full of people just like them, people just like me—in the specific attribute that we share of having a shitload of lived birthdays to our credit. We are old people. And these two friends reported that in the theatre there were virtually no young people. Incredible. And yet, I also know, that isn’t incredible. After all, when I was a young person did I know performers, even incandescent performers, from a half century earlier. Not a chance. I barely knew there had been life a half century earlier. And, with music, I think this situation is more true than in many other domains. Most of us get into listening to music when we are quite young, and as we get older we tend to listen less. And often what we listen to when we are older, is in any case what we listened to when we were younger. So we don’t know much music before when we got started, often not even ten years before, much less from fifty or sixty years before we got started. And often we don’t know much more music after our early days, as well, perhaps twenty years and then silence is not very golden. So it goes. It is not ideal, but I suspect as a broad though of course not universal phenomenon the time-tripping picture is pretty accurate. Thus that few young people turn to A Complete Unknown is not surprising. Why should a teen now, a twenty-something adult now, a thirty something adult now, hell, anyone less than sixty four now, take any time now to even know of Bob Dylan, much less to seriously deep dive into his music? Some old folks might say, well, because Dylan changed music into something it wasn’t. I think it is absolutely true that he did just that regarding duration, focus, lyrics, and more but, even so, some young folks might say, okay, great. I’ll take your word for it. I’m happy to hear he did that. But why do I need to explore it? Why do I need to deep dive into it? That is your pool, not mine. Well, I reply, the truth is, you don’t. I don’t think that Dylan having been historically pivotal to how music has developed is sufficient reason for you to feel a great need to go back and listen. Not to him, or to Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Patti Smith, Joni Mitchell—and so on. You may have historical interest in those who went before and transformed the discipline, and so you may choose to listen deeply way back, and that is fine, of course. But I don’t think it is essential that people go back because of prior historical impact. The same is true and may make the point even more clearly, in many other disciplines. In physics, for example, you don’t have to go back to read Einstein or Dirac, much less Newton and many others who changed the whole field. Yes, they did that, but that means that if you get up to date now, perhaps physics being your thing, then by being up-to-date now, you are imbibing their effects on physics along with more effects of others since. Or, say you love basketball. Do you have to watch old videos of Doctor J, Bill Russell, Bill Walton, and Oscar Robinson to be a fan who legitimately and intelligently enjoys basketball now. The old timers tend to say yes, you do, but I don’t think so. The predecessors’ effects live on in the game. So to experience historical insights, to gain the fullest possible overview, yes, you would have to dig in, but not to enjoy next Tuesday’s playoff game, which is quite alright to do. Is there some other reason to visit the past in diverse fields, including music? Yes, I think there is. For example, you may simply enjoy doing so. History is your drug of choice. Or, time-traveling back, you may be affected by the predecessors’ style and particular genius. This of course applies most powerfully if you are active in the discipline or art, whatever it may be. But what if you just dabble now and then and you mostly enjoy what’s happening now, what’s current, not least because it is what others now enjoy? I think there is still a reason to time-travel in some fields, for some people. Call the destination enjoyment, enrichment, and edification. And so, to potentially accrue those things there is a case, I claim, for listening to Bob Dylan’s music. But such a case requires evidence, not just a claim. No one had heard anything quite like Dylan before Dylan. And I would have to say, we haven’t heard overly much like him since him. Big deal, you might say, everyone is different. Yes, that is true, but some are differently different. That is a big claim, rarely true, I admit. You can decide for yourself if it is true of Dylan, but you can’t do that if you don’t give his work some time. So here I admit that I am trying to provoke attention to Dylan from those who haven’t yet given his work much. For the rest of you, those who have attended to his work, maybe this will be a reminder of why you cared, or just a familiar trip with a few twists. I should perhaps say that for me at least, as a teenager hearing Dylan, what was mesmerizing and edifying like with no other singer song writer included his voice and the ebb and flow of the music under his songs. But beyond those, and those don’t universally appeal even if I can’t perceive why they don’t, for me what was and is mesmerizing, and what I would wager it could be mesmerizing for you too, albeit with some effort to first get into something different, is his incredible lyrics. So what can I say? Am I just a guy with roots way back when who is forever young about this, which in this case could mean forever blind to the scale of subsequent accomplishments? Or am I correct that Dylan’s lyrics, even taken alone, much less taken with the melodies and sonic and social emotions that accompany them, stand out even today as wildly different than what is current—and after sixty years, even as still more enjoyable, enriching, and edifying than most and perhaps even all of the rest? The movie A Complete Unknown addresses just five years of Dylan’s emerging public life. And in those years, it addresses just a few songs, with hundreds more to follow later. What more could the film include about Dylan or his lyrics without becoming endless? The movie addresses some of his life too, one chapter I guess, albeit a very important one, but I will set his life aside. And the movie doesn’t have Dylan’s voice, though Chalamet, I am told, does a profoundly good job. He’s not Dylan, but very good. So I thought I would here take a sort of break from thinking about the deadly orange plague and how to erase it. I thought I would try and help along Chalamet’s wish for the movie—that it bring new ears to Dylan’s music—and to do that, I would try to entertain, enrich, and edify by offering some Dylan lyrics, even without his voice and music. Mostly, I will let the movie largely choose which songs to present…but not entirely. Finally, I hesitate to interject comments with the lyrics, but as I transcribe the lyrics I suspect I may at times be unable to stop myself. If my comments help a little, great. If not, ignore my small part. But take some time for Dylan’s large part. When Leonard Cohen, another incredible poet from the old days who is, I dare say, also worth some of your time in 2025 was asked about Dylan winning the Noble Prize for literature he said, “To me, [the award] is like pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.” I will keep my comments on the mighty big mountain to an absolute minimum, and not just relative to its scale. I would wager that you all expect me to now offer up some of Dylan’s more political early songs, but first how about a quick foray into some of his version of what is so ubiquitous nowadays…four of his relationship songs…even break up / look back songs, though with an edge. It turns out Dylan is not only an observant troubadour, he is also a human. First… consider “Girl from the North Country” which came along after the movie time but refered back to a movie lady, I think… It goes like this: Well, if you’re travelin’ in the north country fair Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline Remember me to one who lives there She once was a true love of mine Well, if you go when the snowflakes storm When the rivers freeze and summer ends Please see if she’s wearing a coat so warm To keep her from the howlin’ winds Please see for me if her hair hangs long, If it rolls and flows all down her breast. Please see for me if her hair hangs long, That’s the way I remember her best. I’m a-wonderin’ if she remembers me at all Many times I’ve often prayed In the darkness of my night In the brightness of my day So if you’re travelin’ in the north country fair Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline Remember me to one who lives there She once was a true love of mine Not overly complex lyrics. Not mind-bending metaphors and images. No need to interject. But still…he can write, already… Next, consider, “All I Really Want to Do,” a song about him and a her—whoever that might have been—and imagine that you heard it as a teenager, before feminism got your attention…in fact before anything much got your attention. I ain’t lookin’ to compete with you Beat or cheat or mistreat you Simplify you, classify you Deny, defy or crucify you All I really want to do Is, baby, be friends with you No, and I ain’t lookin’ to fight with you Frighten you or tighten you Drag you down or drain you down Chain you down or bring you down All I really want to do Is, baby, be friends with you I ain’t lookin’ to block you up Shock or knock or lock you up Analyze you, categorize you Finalize you or advertise you All I really want to do Is, baby, be friends with you I don’t want to straight-face you Race or chase you, track or trace you Or disgrace you or displace you Or define you or confine you All I really want to do Is, baby, be friends with you I don’t want to meet your kin Make you spin or do you in Or select you or dissect you Or inspect you or reject you All I really want to do Is, baby, be friends with you I don’t want to fake you out Take or shake or forsake you out I ain’t lookin’ for you to feel like me See like me or be like me All I really want to do Is, baby, be friends with you. Again, there is nothing hard to fathom in that song, and yet the sentiments, so succinct, are also so relevant and for some maybe even so emulatable. I want to do two more relationship songs, if you will, since even some old folks like me may not know this next one…and then I have to do one that everyone knows…or knew. First, here is the song you most likely have never heard, titled “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window.” It was not in the movie but it was from the same period, or the end of it, the same time as “Positively Fourth Street” another song that displays wit on top of acid, which I will add later, if we have time… If you perhaps think I was over the top putting the word feminism in the same sentence as his song “All I Really Want To Do.” listen to this song from just before feminism freed countless minds…indeed, from before my generation had by and large heard a feminist word. It was sung to a particular woman…but perhaps also to many women, and I would say to all men. So “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window” goes: He sits in your room, his tomb, with a fist full of tacks Preoccupied with his vengeance Cursing the dead that can’t answer him back You know that he has no intentions Of looking your way, unless it’s to say That he needs you to test his inventions I will interject, I heard that, years after it was recorded, and, well, I wondered, is that fair? Are we men really that gross? Then came the chorus: Hey, crawl out your window Come on, don’t say it will ruin you Come on, don’t say he will haunt you You can go back to him any time you want to I interject: Think abused women not easily moving on… The song continues: He looks so truthful, is this how he feels? Trying to peel the moon and expose it With his business-like anger and his bloodhounds that kneel If he needs a third eye, he just grows it He just needs you to talk or to hand him his chalk Or pick it up after he throws it I have to interject: was there a more militant then current critique of sexism that I missed? Caustic Dylan was very caustic indeed. How long did it take me before I could even really hear what he sang in this one? Surely not as a senior in high school, but maybe it planted some seeds. I have to wonder if Dylan himself heard this one, or maybe he just conveyed it from out of the skies. And tell me, do you not think this broad assessment of male misogyny, even with all the gains against such ways that have occurred over the years, still resonates? Is the image you get listening to this much different than your picture of Trump and Musk? The song goes on: Hey, crawl out your window Come on, don’t say it will ruin you Come on, don’t say he will haunt you You can go back to him any time you want to Why does he look so righteous while your face is so changed? Are you frightened of the box you keep him in While his genocide fools and his friends rearrange? Their religion of little tin women To back up their views, but your face is so bruised Come on out, the dark is beginning I interject, I think perhaps it isn’t surprising that this song is barely known at all… It ends: Ah, come on, out your window Come on, don’t say it will ruin you Come on, don’t say he will haunt you You can go back to him any time you want to Of course the women who shortly later re-birthed feminism didn’t need and probably never heard Dylan cajoling involvement, but I did… and I have to admit, I wonder about the women who voted for Trump. Might they hear this before too long as we heard it back then? Note—if it wasn’t already clear—Dylan’s relationship songs are in no way about narrow relationships even if they ostensibly mainly aim to address just those. Is that true, today, too? And now comes Dylan’s most famous song, “Like A Rolling Stone,” which is the one that most immediately, most proximately, changed the whole industry, and now his words are somewhat more complex. He piles images on images and multiple listenings can yield new takes. This song, and the choice to go in your face electric at the time, is really the destination of the movie. Dylan’s move to rock from folk, but we will here have more to present, from a bit earlier, and later, too, after this one. This time it is a wealthy, even a rich woman—or maybe all materially rich women, or maybe everyone who is materially rich, that Dylan is singing to and about. I am not going to repeatedly include the chorus…save for one time. Once upon a time you dressed so fine Threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you? People call say ‘beware doll, you’re bound to fall’ You thought they were all kidding you You used to laugh about Everybody that was hanging out Now you don’t talk so loud Now you don’t seem so proud About having to be scrounging your next meal And now the chorus… How does it feel, how does it feel? To be without a home Like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone Ahh you’ve gone to the finest schools, alright Miss Lonely But you know you only used to get juiced in it Nobody’s ever taught you how to live out on the street And now you’re gonna have to get used to it You say you never compromise With the mystery tramp, but now you realize He’s not selling any alibis As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes And say do you want to make a deal? I interject: Look up “get juiced in it”—which of three or four meanings do you think Dylan meant to evoke, or all of them about the finest schools, or perhaps from another song, about the “old folks home at the college.” Ah you never turned around to see the frowns On the jugglers and the clowns when they all did tricks for you You never understood that it ain’t no good You shouldn’t let other people get your kicks for you You used to ride on a chrome horse with your diplomat Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat Ain’t it hard when you discovered that He really wasn’t where it’s at After he took from you everything he could steal I can’t not interject—here we have men again…a rich one riding a motorcycle not throwing chalk, but still not where it’s at… Ahh princess on a steeple and all the pretty people They’re all drinking, thinking that they’ve got it made Exchanging all precious gifts But you better take your diamond ring, you better pawn it babe You used to be so amused At Napoleon in rags and the language that he used Go to him he calls you, you can’t refuse When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose You’re invisible now, you’ve got no secrets to conceal Okay, Like A Rolling Stone in hand, it’s time to go back a few years to directly consider society…to go back to what he called his finger-pointing songs and I have to wonder would a young person listening to the following offerings now, with Trump in the societal saddle, and with us needing to do something about it, hear these songs not exactly but at least somewhat like I and others heard them sixty years ago? First, consider “Blowin’ in the Wind.” How many roads must a man walk down Before you call him a man? Yes, ’n’ how many seas must a white dove sail Before she sleeps in the sand? Yes, ’n’ how many times must the cannonballs fly Before they’re forever banned? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind The answer is blowin’ in the wind How many years can a mountain exist Before it’s washed to the sea? Yes, ’n’ how many years can some people exist Before they’re allowed to be free? Yes, ’n’ how many times can a man turn his head Pretending he just doesn’t see? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind The answer is blowin’ in the wind How many times must a man look up Before he can see the sky? Yes, ’n’ how many ears must one man have Before he can hear people cry? Yes, ’n’ how many deaths will it take till he knows That too many people have died? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind The answer is blowin’ in the wind No need to interject. No confusion. Finger pointed unambiguously. Next we have “With God On Our Side,” a song certainly sung to my generation. Oh, my name, it ain’t nothin’, my age, it means less The country I come from is called the Midwest I’s taught and brought up there, the laws to abide And that the land that I live in has God on its side Oh, the history books tell it, they tell it so well The cavalries charged, the Indians fell The cavalries charged, the Indians died Oh, the country was young with God on its side The Spanish-American War had its day And the Civil War too was soon laid away And the names of the heroes I was made to memorize With guns in their hands and God on their side The First World War, boys, it came and it went The reason for fightin’ I never did get But I learned to accept it, accept it with pride For you don’t count the dead when God’s on your side The Second World War came to an end We forgave the Germans, and then we were friends Though they murdered six million, in the ovens they fried The Germans now too have God on their side I learned to hate the Russians all through my whole life If another war comes, it’s them we must fight To hate them and fear them, to run and to hide And accept it all bravely with God on my side But now we’ve got weapons of chemical dust If fire them we’re forced to, then fire them we must One push of the button and they shot the world wide And you never ask questions when God’s on your side Through many dark hour I been thinkin’ about this That Jesus Christ was betrayed by a kiss But I can’t think for you, you’ll have to decide Whether Judas Iscariot had God on his side So now as I’m leavin’, I’m weary as hell The confusion I’m feelin’ ain’t no tongue can tell The words fill my head, and they fall to the floor That if God’s on our side, he’ll stop the next war That was early sixties, the civil rights movement was quite real but the anti war movement was just getting up to speed. Dylan was finger pointing. So what should we have felt heading off to school, or off to war? Do you know the Langston Hughes poem: Harlem (A Dream Deferred) What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode? The next song for our survey—still very straight forward—is “Masters of War”—which revealed quite graphically and unsubtly what Dylan then felt, and me too. Come you masters of war You that build the big guns You that build the death planes You that build all the bombs You that hide behind walls You that hide behind desks I just want you to know I can see through your masks You that never done nothin’ But build to destroy You play with my world Like it’s your little toy You put a gun in my hand And you hide from my eyes And you turn and run farther When the fast bullets fly Like Judas of old You lie and deceive A world war can be won You want me to believe But I see through your eyes And I see through your brain Like I see through the water That runs down my drain You fasten all the triggers For the others to fire Then you sit back and watch When the death count gets higher You hide in your mansion While the young people’s blood Flows out of their bodies And is buried in the mud You’ve thrown the worst fear That can ever be hurled Fear to bring children Into the world For threatening my baby Unborn and unnamed You ain’t worth the blood That runs in your veins How much do I know To talk out of turn You might say that I’m young You might say I’m unlearned But there’s one thing I know Though I’m younger than you That even Jesus would never Forgive what you do Let me ask you one question Is your money that good? Will it buy you forgiveness Do you think that it could? I think you will find When your death takes its toll All the money you made Will never buy back your soul And I hope that you die And your death will come soon I’ll follow your casket By the pale afternoon And I’ll watch while you’re lowered Down to your deathbed And I’ll stand over your grave ‘Til I’m sure that you’re dead Imagine you listened to that repeatedly and then you went off to college, or to work, or to wherever. What might happen next for you as the bombs blasted Indochina? Or, today, Gaza? Would you sag like a heavy load, or explode? I first got into Dylan, however, as did a great many people via a song of his, well part of it, anyhow, sung by a group called the Byrds, “Mr. Tambourine Man.” So I think maybe why not include it? Choosing among so much what to convey here is really taxing. How can I not include “Maggies Farm,” she says “sing while you slave and I just get bored,” “When the Ship Comes In,” and “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” “get born, keep warm, short pants, romance, learn to dance, get dressed get blessed, try to be a success, please her, please him, buy gifts don’t steal, don’t lift 20 years of schoolin’ and they put you on the day shift.” “Mr. Tambourine Man” introduces Dylan writing image after image as he leaves his meaning sometimes hard to perceive, much less to hold on to. Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come following you Though I know that evening’s empire has returned into sand Vanished from my hand Left me blindly here to stand, but still not sleeping My weariness amazes me, I’m branded on my feet I have no one to meet And the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming And now the chorus which I won’t keep repeating… Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come following you Take me on a trip upon your magic swirling ship My senses have been stripped My hands can’t feel to grip My toes too numb to step Wait only for my boot heels to be wandering I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade Into my own parade Cast your dancing spell my way, I promise to go under it Though you might hear laughing, spinning, swinging madly across the sun It’s not aimed at anyone It’s just escaping on the run And but for the sky there are no fences facing And if you hear vague traces of skipping reels of rhyme To your tambourine in time It’s just a ragged clown behind I wouldn’t pay it any mind It’s just a shadow you’re seeing that he’s chasing And take me disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind Down the foggy ruins of time Far past the frozen leaves The haunted frightened trees Out to the windy beach Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky With one hand waving free Silhouetted by the sea Circled by the circus sands With all memory and fate Driven deep beneath the waves Let me forget about today until tomorrow Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come following you I won’t burden you with how I thought about that one, after feeling its verses, except to say that as best I could estimate, you can’t play a song on a tambourine and so I thought the the “ancient empty streets too dead for dreaming” were Dylan’s mind at that moment, or at any rate the mind of the part of him that whispered the words to the rest of him—and that his own parade referred to his funeral…but then again, perhaps not. He is, after all, still alive. And his meanings abound. Now I’d like to offer two in between songs, I guess you might call them, in between finger pointing and going way more poetic. This is where the Nobel Prize judges likely looked, I think, to see what this guy had to offer literature. Note though, that to not really finger point, and to even ridicule finger pointing, certainly didn’t mean Dylan was not taking on the world. Actually, it didn’t even mean no more fingers were going to aim where he wanted. First, there was “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” At this point, I think he had partly in mind a nuclear rain as a metaphor and it works if you take it that way now, but it also works having in mind global storms—you know, high water rising and fascism prowling—or really whatever calamitous social crises you want to insert, even though, again, it was sixty years ago that he wrote this and yet even with the quite monumental changes since, it could also have been written ten minutes ago, which is both amazing and rather sad…because it wasn’t. “Hard Rain” went and goes like this: Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son? Oh, where have you been, my darling young one? I’ve stumbled on the side of twelve misty mountains I’ve walked and I’ve crawled on six crooked highways I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, and it’s a hard And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son? Oh, what did you see, my darling young one? I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’ I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’ I saw a white ladder all covered with water I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall And what did you hear, my blue-eyed son? And what did you hear, my darling young one? I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’ Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’ Heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin’ Heard one person starve, I heard many people laughin’ Heard the song of a poet who died in the gutter Heard the sound of a clown who cried in the alley And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall Oh, who did you meet, my blue-eyed son? Who did you meet, my darling young one? I met a young child beside a dead pony I met a white man who walked a black dog I met a young woman whose body was burning I met a young girl, she gave me a rainbow I met one man who was wounded in love I met another man who was wounded with hatred And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall Oh, what’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son? Oh, what’ll you do now, my darling young one? I’m a-goin’ back out ’fore the rain starts a-fallin’ I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest black forest Where the people are many and their hands are all empty Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison Where the executioner’s face is always well hidden Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten Where black is the color, where none is the number And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it Then I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’ But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’ And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall. Not bad to know our song well and reach out widely with it, or so it seemed to me albeit quite a long time after it seemed that way to him. Next is a song I find my mind sending lines from to my typing fingers over and over, right up to now. Images piled on images. It is ”It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), and it goes like this… Darkness at the break of noon Shadows even the silver spoon The handmade blade, the child’s balloon Eclipses both the sun and moon To understand you know too soon There is no sense in trying. Pointed threats, they bluff with scorn Suicide remarks are torn From the fools gold mouthpiece The hollow horn plays wasted words Proves to warn That he not busy being born Is busy dying. Temptation’s page flies out the door You follow, find yourself at war Watch waterfalls of pity roar You feel the moan but unlike before You discover That you’d just be One more person crying. So don’t fear if you hear A foreign sound to your ear It’s alright, Ma, I’m only sighing. As some warn victory, some downfall Private reasons great or small Can be seen in the eyes of those that call To make all that should be killed to crawl While others say don’t hate nothing at all Except hatred. Disillusioned words like bullets bark As human gods aim for their mark Make everything from toy guns that spark To flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark It’s easy to see without looking too far That not much Is really sacred. While preachers preach of evil fates Teachers teach that knowledge waits Can lead to hundred-dollar plates And goodness hides behind its gates But even the President of the United States Sometimes must have To stand naked. And though the rules of the road have been lodged It’s only people’s games that you got to dodge And it’s alright, Ma, I can make it. Advertising signs that con you Into thinking you’re the one That can do what’s never been done That can win what’s never been won Meantime life outside goes on All around you. You lose yourself, you reappear You suddenly find you got nothing to fear Alone you stand with nobody near When a trembling distant voice, unclear Startles your sleeping ears to hear That somebody thinks They really found you. A question in your nerves is lit Yet you know there is no answer fit to satisfy Ensure you not to quit To keep it in your mind and not forget That it is not he or she or them or it That you belong to. But though the masters make the rules For the wise men and the fools I got nothing, Ma, to live up to. For them that must obey authority That they do not respect in any degree Who despise their jobs, their destiny Speak jealously of them that are free Do what they do just to be Nothing more than something They invest in. While some on principles baptize To strict party platforms ties Social clubs in drag disguise Outsiders they can freely criticize Tell nothing except who to idolize And say “God Bless him”. While one who sings with his tongue on fire Gargles in the rat race choir Bent out of shape from society’s pliers Cares not to come up any higher But rather get you down in the hole That he’s in. But I mean no harm nor put fault On anyone that lives in a vault But it’s alright, Ma, if I can’t please him. Old lady judges, watch people in pairs Limited in sex, they dare To push fake morals, insult and stare While money doesn’t talk, it swears Obscenity, who really cares Propaganda, all is phony. While them that defend what they cannot see With a killer’s pride, security It blows the minds most bitterly For them that think death’s honesty Won’t fall upon them naturally Life sometimes Must get lonely. My eyes collide head-on with stuffed graveyards False goals, I scoff At pettiness which plays so rough Walk upside-down inside handcuffs Kick my legs to crash it off Say okay, I have had enough What else can you show me? And if my thought-dreams could be seen They’d probably put my head in a guillotine But it’s alright, Ma, it’s life, and life only. Jeez Ma, during that, after that, I can’t find my voice, but I feel a great need to find my way. All life in a song, with an edge. And what about your thought dreams? Then? Now? Can we implement them? It turns out that in the fifty to sixty years since all that, Dylan has written hundreds more songs for dozens of albums and who knows how many he consigned to a waste basket. I say that just to make evident that if you consider all this and do get interested, there is more to explore. Remember what I said at the outset, about how we get hooked on sounds when young and we don’t really keep up. It applies to me too. One of the more recent songs I did notice was in the nineties… and it is next. After that there is one from still more recently, 2001 I think, that I never heard until preparing for this, and that I never knew existed, and yet he got an Oscar for it as best song in a movie. First: “Dignity” Fat man lookin’ in a blade of steel Thin man lookin’ at his last meal Hollow man lookin’ in a cotton field For dignity Wise man lookin’ in a blade of grass Young man lookin’ in the shadows that pass Poor man lookin’ through painted glass For dignity Somebody got murdered on New Year’s Eve Somebody said dignity was the first to leave I went into the city, went into the town Went into the land of the midnight sun Searchin’ high, searchin’ low Searchin’ everywhere I know Askin’ the cops wherever I go Have you seen dignity? Blind man breakin’ out of a trance Puts both his hands in the pockets of chance Hopin’ to find one circumstance Of dignity I went to the wedding of Mary Lou She said, “I don’t want nobody see me talkin’ to you” Said she could get killed if she told me what she knew About dignity I went down where the vultures feed I would’ve gone deeper, but there wasn’t any need Heard the tongues of angels and the tongues of men Wasn’t any difference to me Chilly wind sharp as a razor blade House on fire, debts unpaid Gonna stand at the window, gonna ask the maid Have you seen dignity? Drinkin’ man listens to the voice he hears In a crowded room full of covered-up mirrors Lookin’ into the lost forgotten years For dignity Met Prince Phillip at the home of the blues Said he’d give me information if his name wasn’t used He wanted money up front, said he was abused By dignity Footprints runnin’ ’cross the silver sand Steps goin’ down into tattoo land I met the sons of darkness and the sons of light In the bordertowns of despair Got no place to fade, got no coat I’m on the rollin’ river in a jerkin’ boat Tryin’ to read a note somebody wrote About dignity Sick man lookin’ for the doctor’s cure Lookin’ at his hands for the lines that were And into every masterpiece of literature For dignity Englishman stranded in the blackheart wind Combin’ his hair back, his future looks thin Bites the bullet and he looks within For dignity Someone showed me a picture and I just laughed Dignity never been photographed I went into the red, went into the black Into the valley of dry bone dreams So many roads, so much at stake So many dead ends, I’m at the edge of the lake Sometimes I wonder what it’s gonna take To find dignity Is not seeking dignity more in play now, even, than then? And for the last song in this episode—I thought writing that, that, I have to stop somewhere. And I thought at first that I would jump forward to 2000 to a song Dylan wrote for the movie “Wonder Boys.” I guess he was about sixty. I had never heard it despite that it got the Oscar. It is called “Things Have Changed.” But then I decided since Dylan changed personas over and over, repeatedly leaving one version of himself and stepping into another version of himself almost as his most constant attribute—always changing—perhaps I ought to convey the song “Positively Fourth Street” which displayed his fierce words again, but this time directed at those who wanted him to never change. The song title refers to a street in Greenwich Village, where he first joined folk singers and then, at least in their feelings, left them, though I would say, not really. You’ve got a lotta nerve to say you are my friend When I was down you just stood there grinnin’ You’ve got a lotta nerve to say you got a helping hand to lend You just want to be on the side that’s winnin’ You say I let you down, ya know its not like that If you’re so hurt, why then don’t you show it? You say you’ve lost your faith, but that’s not where its at You have no faith to lose, and ya know it I know the reason, that you talked behind my back I used to be among the crowd you’re in with Do you take me for such a fool, to think I’d make contact With the one who tries to hide what he don’t know to begin with? You see me on the street, you always act surprised You say “how are you?”, “good luck”, but ya don’t mean it When you know as well as me, you’d rather see me paralyzed Why don’t you just come out once and scream it No, I do not feel that good when I see the heartbreaks you embrace If I was a master thief perhaps I’d rob them And tho I know you’re dissatisfied with your position and your place Don’t you understand, it’s not my problem? I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes And just for that one moment I could be you Yes, I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes You’d know what a drag it is to see you That was Dylan saying goodbye to the Folk music community. Next, in a song titled “Farewell Angelina.” he says goodbye to Joan Baez, I think, and, as well to the then radical activist left community. Notice there is nothing about Baez that repels him. Rather it is something about the times, about our community that repelled him. I think we should have listened to Dylan not only when he said what we liked, but also when he said what he tried to convey here, when he said what he could no longer immerse himself in, what he had to escape. Farewell Angelina The bells of the crown Are being stolen by bandits I must follow the sound The triangle tingles And the trumpets play slow Farewell Angelina The sky is on fire And I must go There’s no need for anger There’s no need for blame There’s nothing to prove Ev’rything’s still the same Just a table standing empty By the edge of the sea Farewell Angelina The sky is trembling And I must leave The jacks and the queens Have forsaked the courtyard Fifty-two gypsies Now file past the guards In the space where the deuce And the ace once ran wild Farewell Angelina The sky is folding I’ll see you in a while See the cross-eyed pirates sitting Perched in the sun Shooting tin cans With a sawed-off shotgun And the neighbors they clap And they cheer with each blast Farewell Angelina The sky’s changing color And I must leave fast King Kong, little elves On the rooftops they dance Valentino-type tangos While the makeup man’s hands Shut the eyes of the dead Not to embarrass anyone Farewell Angelina The sky is embarrassed And I must be gone The machine guns are roaring The puppets heave rocks The fiends nail time bombs To the hands of the clocks Call me any name you like I will never deny it Farewell Angelina The sky is erupting I must go where it’s quiet And so he did and not only Baez but also the movement lost Dylan at least as someone intimately immersed in it and singing for it. It was not her fault at all, I think, but instead the movement’s fault as we shot tin cans and heaved rocks, and I say again that I think we should have heard Dylan not only when he sang what we were ourselves learning and trying to teach, but also when he sang about our not always wonderful effects on others. Next, here is one song not from Dylan but from Baez to him, well after their split. Dylan wasn’t the only one who could write. It is called “Diamonds and Rust.” Well, I’ll be damned Here comes your ghost again But that’s not unusual It’s just that the moon is full And you happened to call And here I sit Hand on the telephone Hearing a voice I’d known A couple of light years ago Heading straight for a fall As I remember your eyes Were bluer than robin’s eggs My poetry was lousy you said Where are you calling from? A booth in the midwest Ten years ago I bought you some cufflinks You brought me something We both know what memories can bring They bring diamonds and rust Well, you burst on the scene Already a legend The unwashed phenomenon The original vagabond You strayed into my arms And there you stayed Temporarily lost at sea The Madonna was yours for free Yes, the girl on the half-shell Could keep you unharmed Now I see you standing With brown leaves falling all around And snow in your hair Now you’re smiling out the window Of that crummy hotel Over Washington Square Our breath comes out white clouds Mingles and hangs in the air Speaking strictly for me We both could have died then and there Now you’re telling me You’re not nostalgic Then give me another word for it You who are so good with words And at keeping things vague ‘Cause I need some of that vagueness now It’s all come back too clearly Yes, I loved you dearly And if you’re offering me diamonds and rust I’ve already paid Okay, I know I said that would be it, but, I guess I lied. Dylan life-switching and dodging his own steps may be catching. At any rate, I don’t see how I can end this without this next song, the final one, I promise. It is called “Chimes of Freedom.” It’s on the album titled Another Side of Bob Dylan from 1964. Dylan was born in 1941, six years before me. So he was at most 23 when he wrote this. Like I said at the beginning, he was differently different… The song goes like this… Far between sundown’s finish an’ midnight’s broken toll We ducked inside the doorway, thunder crashing As majestic bells of bolts struck shadows in the sounds Seeming to be the chimes of freedom flashing Flashing for the warriors whose strength is not to fight Flashing for the refugees on the unarmed road of flight An’ for each an’ ev’ry underdog soldier in the night An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing In the city’s melted furnace, unexpectedly we watched With faces hidden while the walls were tightening As the echo of the wedding bells before the blowin’ rain Dissolved into the bells of the lightning Tolling for the rebel, tolling for the rake Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsaked Tolling for the outcast, burnin’ constantly at stake An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Through the mad mystic hammering of the wild ripping hail The sky cracked its poems in naked wonder That the clinging of the church bells blew far into the breeze Leaving only bells of lightning and its thunder Striking for the gentle, striking for the kind Striking for the guardians and protectors of the mind An’ the unpawned painter behind beyond his rightful time An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Through the wild cathedral evening the rain unraveled tales For the disrobed faceless forms of no position Tolling for the tongues with no place to bring their thoughts All down in taken-for-granted situations Tolling for the deaf an’ blind, tolling for the mute Tolling for the mistreated, mateless mother, the mistitled prostitute For the misdemeanor outlaw, chased an’ cheated by pursuit An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Even though a cloud’s white curtain in a far-off corner flashed An’ the hypnotic splattered mist was slowly lifting Electric light still struck like arrows, fired but for the ones Condemned to drift or else be kept from drifting Tolling for the searching ones, on their speechless, seeking trail For the lonesome-hearted lovers with too personal a tale An’ for each unharmful, gentle soul misplaced inside a jail An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Starry-eyed an’ laughing as I recall when we were caught Trapped by no track of hours for they hanged suspended As we listened one last time an’ we watched with one last look Spellbound an’ swallowed ’til the tolling ended Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones an’ worse An’ for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Whooops, I gotta change my mind again. When the pundits and critics called Dylan the voice of my generation I think the song that they had in mind wasn’t any of those I have cribbed above. It was, instead, “The Times They Are A Changin.” So surely I have to offer that one too… Come gather ’round people Wherever you roam And admit that the waters Around you have grown And accept it that soon You’ll be drenched to the bone If your time to you is worth savin’ And you better start swimmin’ Or you’ll sink like a stone For the times they are a-changin’ Come writers and critics Who prophesize with your pen And keep your eyes wide The chance won’t come again And don’t speak too soon For the wheel’s still in spin And there’s no tellin’ who That it’s namin’ For the loser now Will be later to win For the times they are a-changin’ Come senators, congressmen Please heed the call Don’t stand in the doorway Don’t block up the hall For he that gets hurt Will be he who has stalled The battle outside ragin’ Will soon shake your windows And rattle your walls For the times they are a-changin’ Come mothers and fathers Throughout the land And don’t criticize What you can’t understand Your sons and your daughters Are beyond your command Your old road is rapidly agin’ Please get out of the new one If you can’t lend your hand For the times they are a-changin’ The line it is drawn The curse it is cast The slow one now Will later be fast As the present now Will later be past The order is rapidly fadin’ And the first one now Will later be last For the times they are a-changin’ We still have to make Dylan’s observation real—don’t we? So that’s it. I hope the words will cause you to try some albums. The music and his voice really do add to the brew. Bringing It All Back Home, Highway Sixty One Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde, were three albums done back to back to back, and are as good as any three consecutive artistic interventions, at least in my mind, as ever can be found, and at any rate are as good a place as any to start navigating Dylan, unless, of course, you start earlier—or later. So by all means lend him your ear to help fulfill Chalamet’s hope for the movie’s effect, but do it please only as an adjunct to and maybe to help fuel giving Trump migraines, and worse. Michael Albert is the co-founder of ZNet and Z Magazine. |

Responses:

None

12246

From: ryan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Re: Bobby D and the creative lea

URL: https://www.counterpunch.org/2025/01/03/a-complete-pantsload-hollywoods-latest-biopic-dylan/

|

another point of view...lol... January 3, 2025 A Complete Pantsload: Hollywood’s Latest Biopic (Dylan) Geoff Beckman Poster for A Complete Unknown. A COMPLETE PANTSLOAD (starring Willy Wonka) doesn’t pass even the most casual fact-check. Hollywood has never made biographies of musicians or songwriters that came within six time zones of truth; film buffs who also follow the music industry often get into extended discussions about which film about a famous singer, songwriter or musician is the worst. The saving grace is that a bad movie bio is almost always pretty easy to spot. Lyricist Lorenz Hart was gay (mostly closeted) but he lived with his controlling mother (who knew what her son liked) after his father died. People debate about which psychiatric illness he had (manic-depression, depression or even schizophrenia). He was a blackout drunk who often had episodes (which make a good fix on his psyche especially hard to get). The biopic of his partnership with Richard Rodgers (WORDS AND MUSIC) was made by MGM– by far the company that produced the most saccharine movies. Who did they pick to play a German Jew who wrote lyrics for songs with titles like “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered”? Mickey Rooney, of course. You see that expecting truth and that’s on you. Cole Porter was a wealthy, spendthrift pansexual from Indiana, who attended Harvard Law and roomed with future Secretary of State Dean Acheson until he dropped out. Warner’s chose a reformed cockney acrobat– who’d been born Archie Leach– to depict him. Other than the flamboyance and charm, “Cary Grant” didn’t bring much to that part. (Certainly not singing; Grant, who had some of the same demons that drove Porter, balked at even oblique illustrations of Porter’s sketchiness in NIGHT AND DAY). If you were making a movie, in 1964, about Hiram King “Hank” Williams– a violent alcoholic who abused drugs and beat his wife (some of that due to a congenital, untreatable spinal condition, which led many patients to self-medicate for relief)– which actor would you choose? Williams’s family who bowdlerized the script) picked George Hamilton– and a director of some of Elvis Presley’s worst movies. There’s never been a point where things got appreciably better. Diana Ross works very hard in LADY SINGS THE BLUES– and if you’re willing to grant enough indulgences because Billie Holliday’s life was so tragic– the film succeeds pretty well. Motown didn’t scrimp on the soap opera elements, though– nor did it emphasize any of the interesting details. The best thing you can say for THE BUDDY HOLLY STORY is that it insisted on having the actors learn to play the music and perform live (except for some dubbed-in leads– which were played live). It makes absolutely everything up (to name just one, Holly had a producer– and Norman Petty stole most of his royalties and many of his copyrights). Also, Gary Busey doesn’t even try to mimic Holly’s style. I was a huge Doors fan; I saw almost all the recordings of their live performances and interviews. I would have given Val Kilmer the Best Actor Oscar (thought I would have thought about Robin Williams or Jeff Bridges for THE FISHER KING– and certainly not Anthony Hopkins, with a nice Chianti). Oliver Stone did his usual hackwork on the story (basing the movie on a book written by a teenage staffer of Jim’s didn’t help any, either.) I’m considerably less charitable about JUDY– most likely because I worked in a revival house owned by a gay man during my teens and early 20’s. We played dozens of Judy Garland movies; I grew enormously sick of listening to drunken queens mythologize her– while they played fast and loose with the facts. (The movie is based on a play by a gay man who doesn’t seem to have cared much for the truth; it has a performance by a marginally talented actress who desperately wanted an Oscar– and got one.) DE-LOVELY, the 2004 take on Porter, has the considerable asset of Kevin Kline (Cole Porter used to chew the scenery of every room he entered as well). but the film rather charitably suggests that nothing that happened to Porter was his fault. I SAW THE LIGHT at least admits that Hank Williams drank and he was a hot mess as a human being. It manages to leave the audience with the notion that the prodigiously-gifted songwriter– who battered down the barriers between country blues and pop music– was a marginally-talented hack who got lucky. MAESTRO made my brain hurt. It’s better than the hot messes that are ROCKETMAN and BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY, in that it makes you believe Leonard Bernstein has talent. It’s not terribly good at identifying what his talents were. There is no golden era– no period when movies about musical artists did a great job of depicting their subjects. If you were making a top ten list, you might have to put Jimmy Stewart (in THE GLENN MILLER STORY) or Jennifer Lopez (SELENA) on it. +++ A COMPLETE PANTSLOAD had warning signs all over it. The possibility that any film would be able to capture– much less explore– the myriad contradictions that are Robert Allen Zimmerman was about the same as the odds of the the Cleveland Browns going 17-0 in the 2025 NFL season. You’d have difficulty doing it in a 10-episode miniseries. There’s also the problem with the protagonist. You can endlessly admire his work– and still note that the man who would become Bob Dylan has more than a little of James Gatz in him. If you want to be truly uncharitable, substitute Sammy Glick… or even Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes. To get where he wanted to go, Bobby Zimmerman was prepared to stomp over anyone who got in his way (hiring Albert Grossman was an indicator of what he was willing to do). Young Dylan was documentarized more than once– and he shows a decidedly mean streak in his behavior. Even genuine admirers (Al Kooper, to name one) say that Dylan treated people who did nothing other than admire him beyond measure very badly. And since the movie was directed by James Mangled, you knew there was zero chance of honesty or accuracy. A COMPLTE PANTSLOAD marked the third time Mangled played played fast and loose with real life. People who know the life story of Johnny Cash have few kind words to say about WALK THE LINE. Racing fans detest FORD V FERRARI with a passion that’s almost startling. Mangled uses the same approach to historical drama as Stone– he comes to his subject matter with his mind made up. If the facts get in his way, he alters them (or just makes stuff up) to communicate what he wants to say. Mangled is also too much of an immature dipshit to be able to depict any event that features human beings. One party is always required to be unredeemably evil– the other is pure and good. Giving his hero a few tragic flaws entirely beyong his control is about as far as Mangled goes. he likes simplistic depictions– he lives to give you soap opera plots or TV movie nonsense. +++ People who make bullcrap about real people always say “the audience won’t notice.” My take– from spending long hours in theaters with people who buy tickets– is that they damned well do. Filmgoers might not KNOW they’re being fed a pile of doctored swill– much less be able to identify what is wrong or why. But they can sense that a movie is playing fast and loose with the facts. Distortions made to serve the filmmaker’s purposes almost always give the resulting show an perceptible aura of unreality and lack of substance. As the audience watches events unfold, it has questions– most often about why the character(s) are behaving that way. A movie that makes things up doesn’t answer them– or it pawns off superficial cliches. Often the audience detects a similarity to a play, movie or TV show they’ve already seen. They can’t be positive that something is wrong– but they sense something is being massaged, and the film begins to lose them. When you watch a movie about a famous person that seems to go downhill in the second act, that’s usually the reason why. It can be because the story of how the person made it is more engrossing than what happens after getting there. But often it’s the collective impact of falsehoods great and small mucking up the suspension of your disbelief. My wife knew virtually nothing about the life of Leonard Bernstein, for example, but she knew I did. She kept pausing MAESTRO to ask me specific questions about events. Usually in spots where Bradley Cooper had played fast and loose with the truth. My wife is not a typical viewer (living with me for 20+ years will warp anyone), but I’ve watched moviegoers do post-mortems. In viewing after viewing of Jim Sheridan’s IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER, they’d exit talking to themselves about whether the events shown on screen really happened. (Spoiler alert: Mostly they didn’t.) Mangled always responds to people who raise these points with him– he throws a hissy-fit and says they don’t understand filmmaking, or what he was trying to do. My take: They understand exactly what he did. Bullshit is pretty easy to spot. +++ Let me give you an example– a relatively minor story element from the movie one could call WHITE RAY. Vivian Liberto was a Sicilian Catholic from San Antonio. She was born into a mixed marriage. Her dad’s parents had immigrated to New Orleans from Palermo, Sicily; mom was the daughter of a German-Irish man and a black woman. (This can all be substantiated. There was a TV show that had celebrities taking DNA tests. One of the episodes featured Roseanne Cash.) Vivian’s parents considered her Sicilian-American; she attended white schools– in Texas, so the bar was high. She met a soldier named John Cash when she was 17– when he got sent overseas for three years, they exchanged letters almost every day. He returned to the US when she was 20. She married him and eventually gave him three kids. Cash dragged her to Memphis, Tennessee. Seven years later, he took her to a bucolic region of California, because he’d bought a trailer park in Casitas that he hired his parents to manage. His profession meant he was rarely home– while he was out on tour, he spent most of his time drinking. doing drugs and cheating with every woman he could wrangle. Time passed. Cash made money and his addictions spiraled out of control. Eventually he got arrested on drug charges. On the advice of his manager, Vivian went with him to court; her job was to pretend that they had a happy marriage, and that her husband had just made a minor-one-time mistake. That caused Vivian an endless amount of trouble. Pictures of her were published– and because she was a dark-skinned Italian (who also possessed some of the genes of her mom’s people), she began to get hate mail from Ku Klux Klan types for marrying a white man in an era when interracial marriage was illegal in many states at. (If you want to get a fix on this, check her Wikipedia page– there’s a 1961 photo that gives you an idea why the meme got traction.) Cash dumped her. You can argue this was for the best– that the marriage had been over for years. They never saw each other, they’d stopped liking each other by the early 60’s– and she knew damned well what he was doing. You can also say that Cash had been more than happy to maintain the charade for years– that unless and until he got to pork June Carter, he would have been willing to maintain the fiction endlessly (By the way, Ray Charles Robinson– given the existence of the boxer, you can understand why he dropped his last name– married Della Beatrice Howard in 1955. They didn’t stay married for life– she divorced him in 1977. Contrary to what the movie suggests, he never stopped drinking or smoking dope. Some sources say he only moderated the heroin intake. He had 12 kids, so he never stopped sleeping around.) A less charitable view of what transpired is that Cash and his managers believed that being married to a woman that crackers thought was black was killing his career by making it hard for him to get booked down south. He tried to explain that Texas (not exactly a blue state) considered Vivian white– but people who believe that “one drop of negro blood pollutes you” weren’t buying that Anyway, Cash ended the marriage, left her with the kids and went off with a woman he’d been pursuing for years. He occasionally saw the kids– and virtually never paid child support. Vivian remarried in 1968; since her husband was a cop, the odds against that marriage being happy seem remote. But they stayed married and she wasn’t impoverished anymore. How closely does the real Vivian Cash track James Mangled’s portrait of her? He cast Ginnifer Goodwin (about as WASPy as an actress as you can get) and Goowin plays an utterly unsupportive, full-on shrew. At one point. she even belittles River Phoenix about his decision to have everyone in the band wear black. Mangled claims he never intended to make a documentary– he was portraying the growing love affair between Cash and June Carter. Coulda fooled me. I’ll leave all the other issues for you to investigate, if you choose. +++ I’m not even gonna touch FORD V FERRARI. Racing fans are obsessive by nature; many of them had been dreaming of seeing the story dramatized for decades. Mangled’s depiction spawned many articles– even whole sites– about the liberties taken with the events of the lives of Ken Miles, Carroll Shelby, Henry Ford II and Lee Iacocca, and their personalities and behavior. Mangled had the same response: “I made the movie that matched the story as I saw it.” The possibility that he had his vision circumscribed by the interior of his sigmoid colon has yet to enter Mangled’s mind +++ My take on this– as someone who reads and writes history and enjoys movies and TV– is pretty simple: Don’t go to movies looking for truth. If you want to see a movie– but not get immersed in lies– before you see it, check the Internet. If the person is famous, you probably know enough that you can’t have the story spoiled. People who study the lives of famous folks will explain what the movie gets right (usually wrong) at great length, so you can decide. I’m willing to grant a fair amount of license– because it is difficult to condense a full life into two hours. I do require that at least 50% of a movie be accurate before I give the people who made it my money. If they don’t meet that standard, I’ll stream the movie and they can have whatever they sold it to the service for. But they don’t get my money directly. My advice to filmmakers? If you don’t want to stick to the facts– if you want to (as the newspaper guy says in THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE) “print the legend”, do what Hollywood used to do (or LAW & ORDER– is that is still on the air?– does): Make a movie BASED on the story where you change all the names, so nobody gets the impression this is what actually happened. There’s nothing wrong with that– you can make a pretty decent film. INHERIT THE WIND isn’t even close to “Tennessee v John Scopes”– but thanks to Spencer Tracy, Frederic March, Gene Kelly and Henry Morgan, it’s still a corking good show. But I object like hell to what Mangled does. It isn’t comparable to what Donald Trump does, but he’s another form of the sustained assault on the truth people have to wade through.” |

Responses:

None

[ Music and Art ] [ Main Menu ]