[ Music and Art ] [ Main Menu ]

11039

From: ryan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: The Enigma of Rickie Lee Jones

URL: https://tedgioia.substack.com/p/the-engima-of-rickie-lee-jones

|

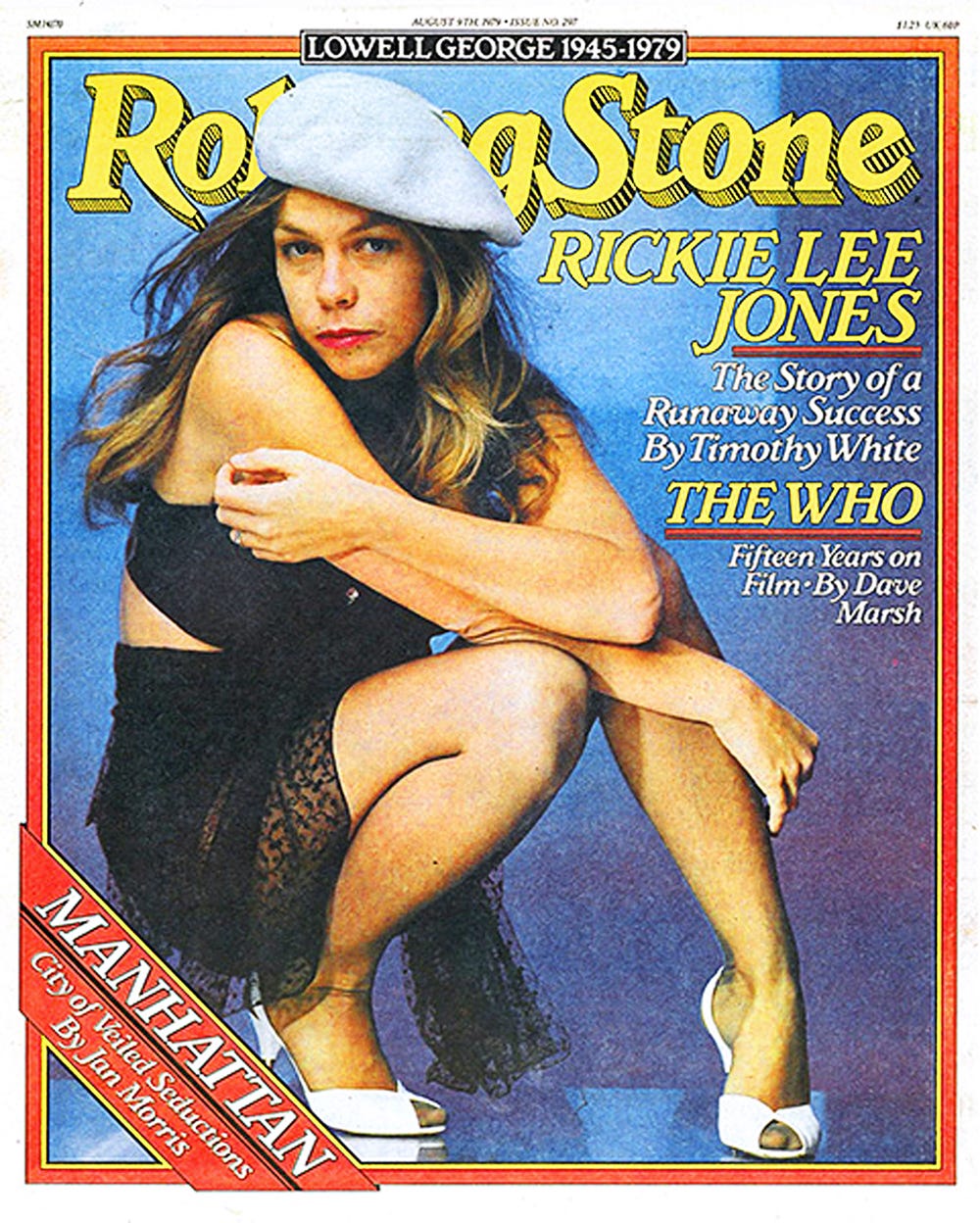

always have loved rickie lee... The Enigma of Rickie Lee Jones I. There are many ways to approach the story of Rickie Lee Jones. But let’s start with an anecdote from studio drummer Jeff Porcaro, who was called in as session player on RLJ’s second album Pirates—allegedly because Jones had admired his brush work at a previous encounter. Porcaro, a legend in the world of studio musicians, later recounted the story: “What a great thing. I go to the session, it's Chuck Rainey on bass, Dean Parks on guitar, Russell Ferrante on piano, Lenny Castro on percussion, and Rickie Lee Jones playing piano and singing. The drums are in an isolation booth with a big glass going across so I can see everybody in the main studio. I have my headphones on, and we start going over the first song. After the first pass of the tune, Rickie Lee in the phones goes, ‘Mr. Porcaro, I know you're known for keeping good time, but on these sessions, I can't have you do that. With my music, when I'm telling my story, I like things to speed up and slow down, and I like people to follow me.’” Porcaro, a consummate professional, asks the engineer to give him more of Jones’s vocal in his headphones so he can follow her rhythmic shifts. The band starts the song again—but Jones stops it halfway through and tells the drummer: “The time is too straight. You gotta loosen up a bit.” Porcaro apologizes, and asks for still more of the vocal track in his headphone mix. On the next take, he focuses closely on Jones’s singing, speeding up and slowing down in response to every twist and turn. But RLJ is still displeased. She halts the take and starts complaining again about the beat. Now every musician on the date—a group of all-star studio players—is tense and anxious. The next take is so unsettled that the producer calls a break. After the break, the band switches to another song—to try to get their mojo back. Pocaro describes what happened next: “So we start laying the track down, and I come up to this simple fill: triplets over one bar. It's written out on my music, and I play the fill. She stops. She says, You have to play harder. . . . Everybody looks at me. I look at everybody. I go, ‘Okay, let's do it again.’ We start again. One bar before the fill, I hear, louder than hell in my phones, We're coming up to the fill. Remember to play hard, while we're grooving. I whack the mess out of my drums, as hard as I've ever hit anything in my life. While I'm hitting them, she's screaming, Harder! I stop. She stops. I'm looking at my drums. My heads have dents in them; if I hit the drum lightly, it will buzz, and I'm pissed. I'm steaming inside. I'm thinking, ‘Nobody talks to me that way.’ [Producer] Lenny Waronker says, ‘Let's do it again.’ We start again, and everybody is looking at me while they are playing. We're coming up to the fill, and she goes, Play hard! and I take my sticks like daggers and I do the fill, except I stab holes through my tom-tom heads. I land on my snare drum, both sticks are shaking, vibrating, bouncing on the snare drum. “I get up and pick up my gig bag. There's complete silence. I slide open the sliding glass door, walk past her, down the hallway, get in my car, and I drive home.” In the aftermath, Porcaro heard from another musician that Jones might sue him—but she let the incident pass. Pirates was eventually released, to critical acclaim, with Steve Gadd, another studio legend, handling much of the drum work. But here’s the best part of the story. Three years later, Porcaro gets a call from a producer asking him to play on a Rickie Lee Jones session for the album The Magazine. This can’t be true, he thinks—has she forgotten their previous encounter? Maybe she was going through a bad spell back then, and doesn’t even remember the details? So Porcaro, taking pride in his professionalism and unwilling to hold grudges, decides to do the date, and see what happens. When he shows up, Rickie Lee Jones greets him like an old friend: “Hi, Jeff, good to see you again. You seem to have lost weight.” The session takes place effortlessly and with excellent results. At the conclusion of the second song, Jones walks up to his drum kit, and in front of all the musicians—some who had been in attendance at the Pirates debacle—told Porcaro: "Jeff, I really have to tell you this. No drummer has ever played so great for me, listened to my music so closely, understood what I'm saying with lyrics, and has followed me as well as you. I just want to thank you for the good tracks." Porcaro’s reaction: “I almost broke up laughing because I had played no differently for her the year before.” II. But by the time of this second session with Porcaro in 1984, Rickie Lee Jones—the rising star whose creativity and artistry had, just a short while before, seemed to promise (or even demand) a long career at the top of the music business—had already seen her moment come and go, at least from the point of view of the industry. She wasn’t even thirty years old, but the critics were no longer charmed by her capriciousness. When The Magazine was released, the New York Times responded: “Miss Jones is still looking for direction.” But even casual fans could tell something was wrong. In the five years after the release of her million-selling debut album Rickie Lee Jones, this hot new songwriter only released one album and an EP —a total of 67 minutes and 11 seconds of music. Do the math: that works out to 13 minutes of new music per year. Clearly Jones was focused on something besides composing and recording. But, whatever her reasons, most of her audience had left, never to return. You can measure the impact on the Billboard chart Rickie Lee Jones (1979) peaked at number 3 on the US album chart. Her follow-up Pirates reached as high as number 5. The Magazine topped out at number 44. The follow-up Flying Cowboys did somewhat better, reaching number 39. But with Pop Pop, recorded in 1989, Jones got no higher than number 121. The days of hit albums and large audiences were over, and they wouldn’t be coming back coming back. In retrospect, her commercial high point as a pop star was her first album, which produced her only genuine radio hit, “Chuck E.’s in Love.” Rickie Lee Jones’s New Memoir Last Chance Texaco, and My RLJ Playlist This is a familiar story in the music business—a promising debut followed by disappointment. So why am I so troubled by the fall of Rickie Lee Jones? There’s a simple answer: her talent was extraordinary. She seemed poised not only to have hit songs—which, after all, aren’t a rarity in the entertainment world—but do something even more remarkable, namely redefine the parameters of pop singing. Her studio battle with Porcaro is all too revealing on this front, and it’s why I started my account by relating it. Rickie Lee Jones had a different concept of time than the other singers. She could make it seem as if her voice was floating over the ground beat with the freshness and changeability of the shifting colors of a sunset. This is something you occasionally find in jazz, but even there it’s a rarity: few improvisers can force the beat into such total submission to their artistic vision. But Jones seemed to do it effortlessly—at least for a time. I’ve heard some express the opinion that Rickie Lee Jones might have had more staying power if she had ditched all those fancy LA studio musicians and brought in seasoned jazz stylists for her record dates—something akin to the kind of sessions Norman Granz produced for Billie Holiday in the 1950s. I’m not sure that would have worked over the long term, if only because Rickie Lee Jones’s biggest obstacles came away from the piano and the microphone. But it would have been extraordinary to hear her working with, say, Jimmy Rowles or Paul Motian or Fred Hersch or Geri Allen as producers. Maybe that’s just dreaming, but what a lovely dream. The sad reality is that her declining sales were the result, to some extent, of her growing affinity for jazz. Her final exile from the Billboard top 100 albums came in response to the unabashed jazz sensibility of Pop Pop (1989). In this regard, Jones experienced the same backlash that ended Joni Mitchell’s run of hit albums after the release of her jazzy Mingus album. Before Mingus, every new Joni Mitchell album seemed destined to get into the top 20 on the chart—afterwards none of them would. But for Rickie Lee Jones, the decline was sharper and less forgiving. After all, Mitchell was embraced by the jazz community—Herbie Hancock even won a Grammy for Album of the Year with his River: The Joni Letters (2007). Rickie Lee Jones, in contract, rarely received that kind of cherishing and celebration from jazz insiders—although she had perhaps the jazziest ways of phrasing of any pop music star during the second half of the twentieth century. Yet this rhythmic flexibility was only part of Rickie Lee Jones’s innovative approach to singing. She also had a way of moving from singing to spoken speech and back again, while handling every gradation along the way. Listen again to her breakout hit, “Chuck E.’s in Love,” cueing the track at the 1:30 point, and hear what she does in the next thirty seconds. Was anyone else doing this in pop music? The short answer is: No, not even close. “In the following couple of years, I was voted Best Rock, Best Pop, and Best Jazz in polls from Playboy to Rolling Stone,” Jones recalls in her new memoir Last Chance Texaco. “I was nominated for five Grammy awards, including Best Album, Best Song, Best Rock Vocal and Best Pop Vocal, and Best New Artist, which I won.” Bob Dylan tracked her down backstage and told her: “Don’t ever quit. You are a real poet.” It seemed like Jones’s destiny was set. She was a sensation on Saturday Night Live. She showed up on the cover of Rolling Stone, with photo by Annie Leibovitz, and it was the bestselling issues in the magazine’s history. When she went on the road, every concert sold out.  They called her the Duchess of Coolsville. And if anyone deserved the title it was Rickie Lee Jones. Almost everything she touched back then was bewitching. Consider the sassy in-your-face delivery of “Danny’s All-Star Joint”—which almost invents its own new genre, a cross between street poetry and juke joint dance tune. But then Jones could turn on a dime and deliver an emotionally riveting ballad such as “On Saturday Afternoon in 1963” or “Coolsville.” Perhaps she lacked the shifting harmonic centers of Joni Mitchell or the vocal range of Aretha Franklin, but there was so much in her arsenal that was one-of-a-kind. She wrote brash, imaginative lyrics. She sang vamp songs like she had invented the concept. Her sense of dynamics was non-pareil. Above all, the confessional tone Jones created with these radical shifts in the symmetry and tone of her music pulled on your heartstrings. These are the virtues that animate the best tracks on her 1980s albums, especially Pirates from 1981, which still shivers my timbers after all these years. Yet, increasingly over the course of the decade, Jones started showing the strain of her rule-breaking lifestyle or, even worse, seemed to be trying too hard—a perennial, if forgivable curse of performers who face the challenge of holding on to those auditorium-filling audiences. Her record producers didn’t help, backing her with oceans of hot and churning instrumental sound, and too often forgetting how important Jones’s voice was in creating the spell of her songs. That distinctive voice was rarely given enough presence in the final mix—it was like Jeff Porcaro’s headset problems all over again—and not only does she need to sing louder to propel the song on its intended journey, but the soft end of her dynamic range, so essential to the conversational effect of her delivery, was taken away from her. The title track from Pirates tries to capture the same jaunty rhythm as the bestselling “Chuck E.’s in Love,” but with 50% more decibels from the band. The formula simply doesn’t work as well, although Jones makes the best she can of the situation and still delivers an impassioned performance. Or listen, for example, to “Ghetto of My Mind” from Flying Cowboys or “Gravity”from The Magazine, and try to figure out why the microphone of the star singer isn’t given more of a boost. Even when she was singing with just solo piano accompaniment, as in the opening of “Hey, Bub” from Girl at Her Volcano, the keyboard gets far too much prominence at the expense of the lyrics, now barely comprehensible at times given their placement in the soundscape. When given more obliging support, she could still shine. Check out Jones’s duet with Dr. John on “Makin’ Whoopee!” from the 1989 album In a Sentimental Mood, and cherish how she bounces over the accompaniment (with a chart by Ralph Burns, who first made his name writing for the Woody Herman band). But it’s revealing that this wasn’t one of her own albums, where the cast of musicians sometimes sounded like potential mutineers on Jones’s piratical outings. “The Horses,” the opening track of Flying Cowboy could be a stellar track, but the orchestra is so dominating, Jones needs to project at the top of her volume to get heard over the accompaniment—and you’re left wondering whether they shouldn’t have just released a piano demo recorded with two mics. (For comparison, listen to the stark, acoustic version of “The Horses” from Naked Songs Live and Acoustic from 1994, to savor how different this song sounds when presented with more intimacy.) In all fairness, Jones didn’t help matters with her lifestyle excesses. “My drug career was short-lived—three years from 1980 to 1983,” she writes in her new memoir Last Chance Texaco. Then adds: “I did drugs like I did everything else. On fire, with no back door.” But the drinking may have done just as much damage. “I was sober from drugs but then I started drinking,” Jones later explained in an interview in Vanity Fair. How much did this impact her work? It’s hard to say, but a reviewer in attendance at Jones’s 1982 Berkeley concert noted the “Jack Daniel’s swigged when she wasn’t forcing it on the band members or passing it out in Dixie cups to the audience.” If the drinking was such a prominent part of her music-making onstage, what toll was it taking in private? The Vanity Fair interview continues: “Was the drinking affecting your tour?” “At the time I had an apartment in New Orleans, so I was thinking that I was bringing my New Orleans party onstage. I thought, Janis Joplin drank onstage, why can’t I? What’s her name, the beautiful British girl with the hair?” “Amy Winehouse?” “I haven’t seen her [perform], but I was probably like Amy Winehouse too bawdy, too raucous. The way people saw me, the singer-songwriter, the expectations of behavior—I wanted to defy that right away, that’s why I went for that stripper look. I wanted to open it up.” I note that this interview was published one day before Amy Winehouse’s death. But Jones doesn’t comment on the fact that Janis Joplin had already died at the age of 27 (the same as Winehouse, it would turn out). Jones had a happier fate, but her music didn’t. After age 27, she still was capable of magic—although not with the kind of consistency we expect from our music legends. The music industry, for its part, had moved on to punk, disco, new wave and other sounds a world apart from the singer-songwriter styles that had dominated the previous era. III. At this juncture, Rickie Lee Jones made a more overt commitment to jazz. She had always been jazzy, but in a kind of offhanded way, undercutting the pop sensibility of the finished product. But she now started recording songs that were sometimes 40 or 50 years old, if not older. And she was tackling the really difficult jazz ballads—complex, world-weary quasi-art songs such as “Lush Life” or “Something Cool.” You have to give her credit for boldness. Not even Joni Mitchell was pushing her jazz sensibilities this far. And Jones definitely had an affinity for this music. Even so, her voice was now sometimes showing a shrillness that limited her expressive capabilities—listen to “Lush Life” for an example—and she was tackling classic works that inevitably demanded comparison with Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday and others who specialized in this same repertoire. The final results were not without distinction—Jones ultimately does earn our respect as an interpreter of the standard repertoire. But these tracks would neither bring her acclaim among jazz insiders, nor help retain her dwindling mass market audience. She was now doing more covers versions than composing now—a trend that would continue from this point on in her career. Given her exceptional songwriting talent, this was quite a loss. I haven’t done a statistical analysis, but my guess is that more than two-thirds of the tracks Jones released between 1990 and 2000 were either a cover song or a re-recording of one of her older tracks. There are moving performances here, but you don’t triumph over the pop music world by recording “Bye Bye Blackbird” or “Autumn Leaves.” It would be wrong to convey the sense of an unmitigated decline. The Evening of My Best Day (2003) marked a successful return to the singer-songwriter conception of her best early work, but drawing on musicians (Bill Frisell, Kenny Wollesen, Nels Cline, etc.) better able to give her support without overwhelming her quirky personal sound. But when this was released, Jones was a few months shy of her 50th birthday, and even fans with long memories had stopped waiting for a Rickie Lee Jones comeback. The chosen single to promote the album, hopefully entitled “Second Chance,” didn’t even chart. For Jones, there would be no more chances at the top. It was no coincidence that her next album was Duchess of Coolsville, an anthology of past glories. These at least wouldn’t fade. Her next studio album, The Sermon on Exposition Boulevard (2007), was an explicitly Christian project based on Lee Cantelon's book The Words, which aimed to restate the teachings of Jesus Christ in unadorned modern language. A project of this sort would not reach a crossover audience under the best of circumstances, but the musicianship and production values were the weakest in Jones’s career to date. The spiritual theme continued with The Balm in Gilead from 2009. But just when fans thought they at least understood Jones’s new worldview, she started her next studio project The Devil You Know with “Sympathy for the Devil.” You got the sense that new albums at this stage in RLJ’s career, were designed more for the artist’s own personal path of discovery and healing, and not targeted at (in the quaint industry terminology) brand expansion. And perhaps that’s not a bad place for a creative artist to arrive at. Another famous Ricky—Nelson, in this instance—even staged a surprising comeback after announcing in a song: “You can’t please everyone, so you got to please yourself.” Then added: “If memories were all I sang, I’d rather drive a truck.” There would be no comeback for Rickie Lee Jones, but at least she wasn’t recycling old songs in Vegas casinos and on cruise trips for retirees. Music is a cruel vocation, and what happened to Rickie Lee Jones is not unusual. Perhaps the real mystery is why fans expect anything different from an entertainment business so obsessed with celebrating youth. But the one virtue of the recording medium is that youth is preserved eternally in its time-resisting tracks. And this provides a balm to all, both artists and listeners. Even those with the most unhappy ends—Elvis or Prince or Lennon or Joplin—enjoy the eternal brashness and confidence of their first artistic blossoming, held forever between the grooves, for at least as long as vinyl and playlists last. And in that regard, Rickie Lee Jones is well served. At her best, in the grand period of ascendancy and for a short while after, she did something fresh and uncluttered and spontaneous and beautiful. Something no else could do. It was so special, even she couldn’t hold on to it. It may be gone when measured on the calendar or clock, but the music itself is still there—that world where RLJ was sits at the top, a place where she absolutely and perfectly belongs. That’s how I prefer to remember her, and with those songs playing, her reign as Duchess of Coolsville can go on forever. Here’s a link to my Qobuz playlist of favorite Rickie Lee Jones tracks. The Enigma of Rickie Lee Jones Ted Gioia May 4 11 11 The Enigma of Rickie Lee Jones I. There are many ways to approach the story of Rickie Lee Jones. But let’s start with an anecdote from studio drummer Jeff Porcaro, who was called in as session player on RLJ’s second album Pirates—allegedly because Jones had admired his brush work at a previous session. Read → Doug Lockwood19 hr agoLiked by Ted Gioia Very interesting piece although you neglected to mention the beautiful album of original material called ‘Traffic from Paradise’ and the incredible trip-hop album ‘Ghostyhead’: her tour for this record was one of the most electrifying evenings of theatre I have ever experienced! 2Reply author Ted Gioia17 hr ago Thanks for the comment. I did include a track from Traffic from Paradise on my Qobuz playlist that accompanies the article. For some reason Ghostyhead doesn't seem to be available on Qobuz—in fact, it might not be on other streaming platforms either. Which is a shame. Reply Patrick S. Noonan1 hr agoLiked by Ted Gioia The appearance of the great Leo Kottke on that album was a great surprise and a continuing delight. 1Reply Patrick S. Noonan1 hr agoLiked by Ted Gioia Terrific summary, Ted. I was recently talking to a band-mate of mine, one of NOLA's go-to bass players, James Singleton, about his sessions with Ricki Lee. Those are his tales to tell, not mine - so I'll just say that she's nothing if not consistent in her singular vision and determination, and how that challenges and impacts her collaborators. 1Reply Tttttt6 hr agoLiked by Ted Gioia Saw her at the Academy of Music , phila in 1982.Woody and Dutch. 1Reply Andrew GilbertMay 4Liked by Ted Gioia I loved this piece Ted...wondering what you thought of her memoir. The singular nature of that first album (and I’d say Pirates, too) makes a lot more sense with her account of absorbing so much pre-WW2 popular music, vaudeville and Broadway (the reoccurring paeans to West Side Story were wonderful and for me surprising). Overall it’s a very impressive book and the first two thirds make for gripping reading. Sudden fame and addiction leave little room for music, and the last third gets fuzzy and loses focus. 1Reply author Ted GioiaMay 4 Her book is fascinating. I initially thought I would write a review of it—then I decided to do a survey of her music and career instead. But I learned a lot from her recounting of events. I wouldn’t have written this piece if she hadn’t published her memoir. 1Reply John GennariMay 5Liked by Ted Gioia Great piece, Ted. I'm writing an essay on Steely Dan that I frame with RLJ's touching and smart eulogy for Walter Becker in RS. I see her cover of "Show Biz Kids" makes your playlist. Good choice. 1Reply author Ted GioiaMay 5 Let me know when your Steely Dan essay runs. I'd like to read it. Reply Robert VaripapaMay 4Liked by Ted Gioia Great write up. I remember when she appeared with her first album and was in love. Wonderful overview of her music and career! PS: Created an Apple Music playlist based on your list at https://music.apple.com/us/playlist/rickie-lee-jones-by-tedgioia/pl.u-ovZAgTZoAN 2Reply RobbMay 4Liked by Ted Gioia An exceptional piece of music writing, bravo. 1Reply © 2021 Ted Gioia. See privacy, terms and information collection notice Publish on Substack |

Responses:

[11041]

11041

From: Mitra, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Lightening

|

I was third row center at a concert she gave in '79. Was astonished at her talent, hours of multi~dimensional amazement. Thanks for the article. |

Responses:

None

[ Music and Art ] [ Main Menu ]