[ Earthwatchers ] [ Main Menu ]

95688

From: Redhart, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Simultaneous rupture of San Andreas and San Jacinto fault history

URL: https://temblor.net/earthquake-insights/north-of-los-angeles-faults-share-earthquakes-13755/

|

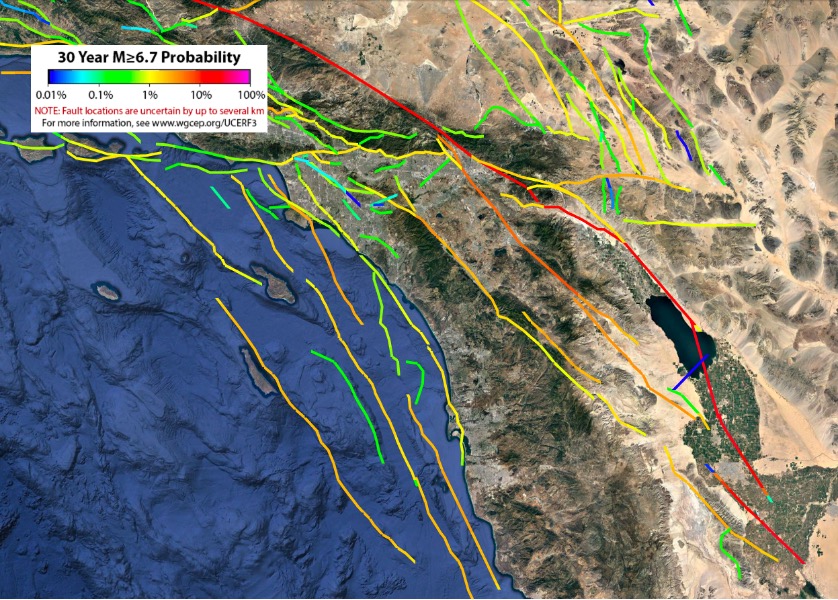

North of Los Angeles, Faults Share Earthquakes POSTED ON FEBRUARY 2, 2022 BY TEMBLOR The San Andreas and the San Jacinto faults have simultaneously ruptured in at least three earthquakes over the past 2000 years. By Alba M. Rodriguez Padilla, Ph.D. candidate, UC Davis (@_absrp) Citation: Rodriguez Padilla, A.M., 2022, North of Los Angeles, Faults Share Earthquakes , Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.235 At the base of the San Bernardino Mountains, U.S. Highway 15 steps over the San Jacinto Fault as it climbs northward into Cajon Pass, where the road sharply turns and crosses the San Andreas Fault. In this mountain divide, these major faults come within 2.5 kilometers of one another. Theoretically, an earthquake on one fault could grow to a larger temblor if the rupture jumps through the pass onto the other. But until now, scientists had not found any direct geologic evidence of such a leap. A new study, recently published in Geology, has uncovered a history of these quakes, highlighting the prevalence of this hazard in Southern California. Digging for ancient earthquakes in a challenging setting Earthquake scientists hunt for evidence of past earthquakes in the dirt. Large trenches, dug across faults, can expose sediment layers offset by movement along a fault during ancient earthquakes. Paleoseismologists can measure 14C in tiny charcoal samples from the sediments to determine when the quakes occurred. Unfortunately, at Cajon Pass, the San Andreas and the San Jacinto faults are hidden at the bottom of valleys filled with large boulders drained from the San Gabriel Mountains, making it difficult to pin down exactly where to dig. This is particularly difficult for the San Jacinto. Also, without fine sediments, trenching is nearly impossible, so scientists have not been able to establish a chronology of past earthquakes. Our team of researchers from the University of California, Davis and San Diego State University discovered a tiny fault perched on top of Lytle Creek Ridge, located near the southern end of Cajon Pass. The “Lytle Creek Ridge Fault” spans the gap between the San Andreas and the San Jacinto faults. Because the fault is small and extends to only about one kilometer depth, it is too shallow and too short to generate its own earthquakes. It is, however, uniquely positioned to be triggered — or forced to move — only when both the San Andreas and the San Jacinto faults are rupturing together. Such a “passenger fault” does not transfer the earthquake between the two large faults, rather it sits as a conveniently located passive recorder of the event. Fortunately, this fault has a clear surface exposure and enough fine sediment to be trenched, unlike the large faults. A history of leaping quakes We dug a trench by hand across the Lytle Creek Ridge Fault, and exposed offset sedimentary layers. 14C dates from these sediments show that three earthquakes have jumped through Cajon Pass in the past 2,000 years. Most recently, the 1812 San Juan Capistrano event spanned the gap. We numerically simulated the 1812 event and compared the amount of offset, or slip, calculated with the amount of slip between layers in our trench from the most recent event. The results confirmed that the events were one and the same. They also showed that the amount of slip that occurred on the San Jacinto fault dropped dramatically as the rupture approached Cajon Pass. Multi-fault earthquakes are a key ingredient in hazard assessment Our team compared the number of events observed in the Lytle Creek Ridge trench to the number of earthquakes in the nearest trenches north and south of Cajon Pass on the San Andreas and the San Jacinto respectively (Scharer et al., 2007; Onderdonk et al., 2018). Through this exercise, we found that 20-23% of earthquakes on the San Andreas and the San Jacinto faults are shared events that jumped faults at Cajon Pass. Earthquakes that span multiple faults can produce greater magnitude events than earthquakes confined to a single fault, leading to longer and more widespread strong ground shaking. Their recurrence in Cajon Pass reshapes the probability of future earthquakes in Southern California. The frequency of events estimated in our study, as well as the characteristics of those events stemming from our models, may be incorporated into the next generation of earthquake-hazard assessment, which helps, among many other things, to set insurance costs. |

Responses:

[95691]

95691

From: ryan, [DNS_Address]

Subject: Re: Simultaneous rupture of San Andreas and San Jacinto fault history

| at least the last quake of the 3 was just 200 years ago so probably will be a while before another such event...but the probabilities on that map are sobering... |

Responses:

None

[ Earthwatchers ] [ Main Menu ]